I finally got around to watching “Food, Inc.” I was floored to see what poultry producers actually go through. Is this really what’s behind the chicken on my plate?

Thanks!

Karen

Pennsylvania

What makes “good food” good? For many, it’s knowing where the food was grown, by whom and how. For instance, is it organic? Is it supporting the local community? Were animals treated well?

But most of us don’t think about how the farmer was treated. We probably don’t think about power, fairness or justice when we’re roaming the grocery aisle or staring at a restaurant menu. And yet, the ability of family farmers to make a good living and have a fair shake in the marketplace has everything to do with the fate of our food, our environment, and our health.

As Farm Aid President Willie Nelson has said, “Our food system belongs in the hands of many family farmers, not under the control of a handful of corporations.” Few U.S. farmers feel the squeeze as much as poultry growers. Their struggle mostly goes on silently, but the conditions they face in a marketplace dominated by huge corporations should leave a bad taste in your mouth.

The Poultry Powerhouses

Today the average American consumes 84 pounds of chicken each year, making it the most popular meat in the U.S. Not only is that a hefty bit of poultry—it’s also more than twice the amount of chicken we ate 40 years ago.

Behind that growing appetite are some big changes in the poultry industry, where chicken products move from chick to chicken nugget. Since the 1950s, the number of chickens raised in the U.S. has skyrocketed by over 1,400 percent, while the number of poultry farmers has plummeted by 98 percent.

Today, the U.S. poultry industry is the most concentrated sector in our food system, not just in terms of the number of farms, but more importantly, with regard to corporate powerhouses who rule the roost. In fact, the top four poultry firms in the U.S.—Pilgrim’s Pride, Tyson, Purdue, and Sanderson Farms—control almost 60% of the market. That scenario is bad enough for family poultry growers, but economists believe that at the local level, markets are much more concentrated, with most growers having only one or two buyers to sell to.

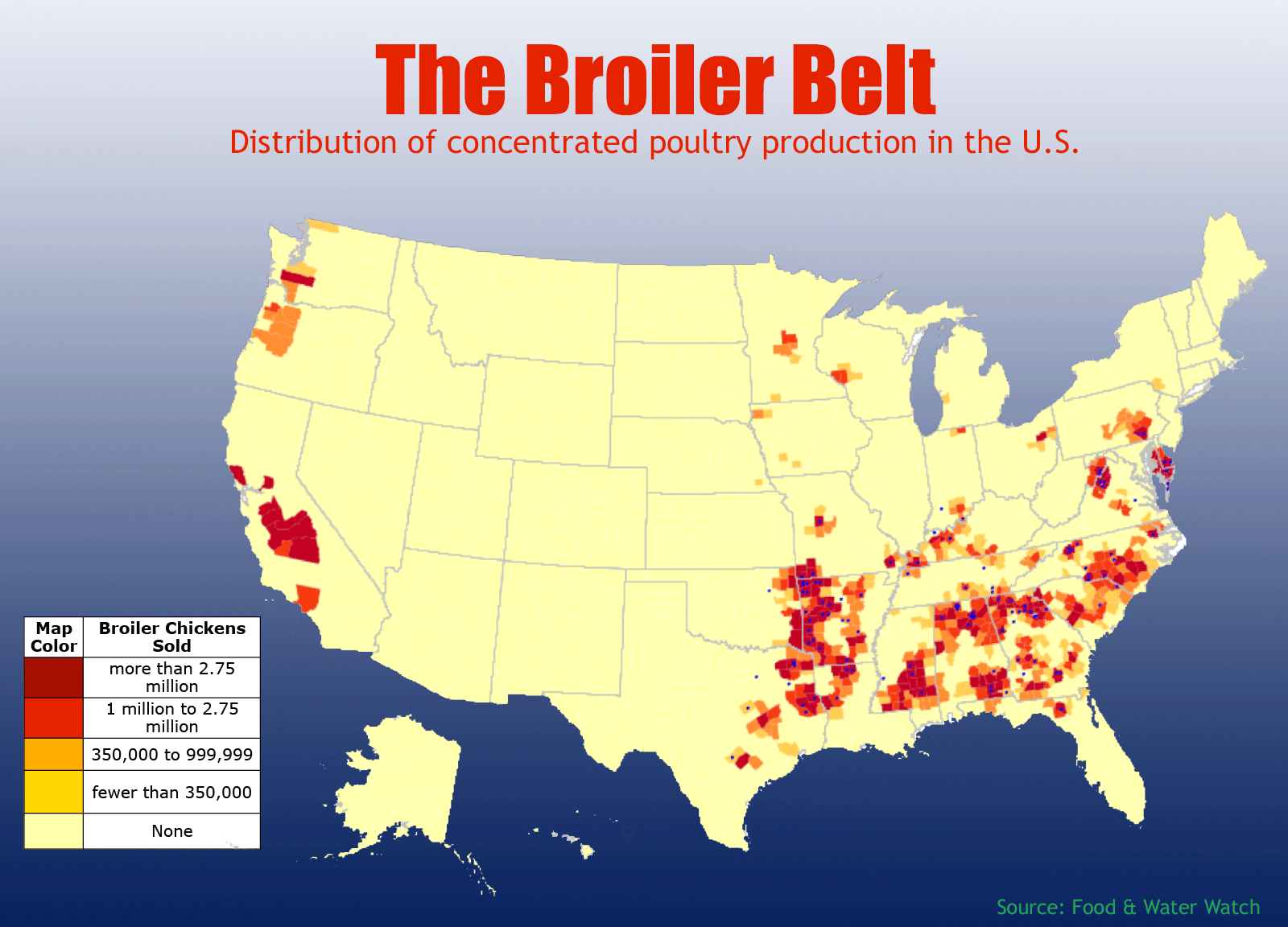

That leaves poultry growers, mostly located in the “Broiler Belt” (a region extending from eastern Texas up to the Delmarva Peninsula on the eastern seaboard) in a state of virtual bondage. We wish we were exaggerating. Check out this clip from Food Inc., to hear poultry grower Carole Morison give the scoop on the industry:

Life Under Contract

So how exactly do big corporations secure their power over farmers? In the poultry industry, the answer is contracts.

When the economy works properly, producers can sell their goods on an open market, having access to multiple buyers with whom they can negotiate the price they receive for their goods. But open, competitive markets for poultry products haven’t existed in a long time. According to the USDA, in 1950, 95 percent of broiler producers were independent (broilers are chickens raised for meat consumption, while layers are those that are raised to lay eggs). Just five years later, independent growers accounted for only 10 percent of the industry, with most growers selling their goods under contract with a company, called an “integrator.” That structure persists today.

Integrators own localized complexes that include feed mills, hatcheries, slaughter plants, and other processing facilities. They contract with local farmers to grow the birds to market weight, while they provide them with all the inputs to do so. So, while the farmer does the work of raising the birds, the birds themselves, their feed, their slaughtering and other elements of production are consolidated under a single company—a scenario called “vertical integration.”

As integrators amassed power, their contracts, which once offered market stability for growers under mutually beneficial agreements, became the tools through which companies could exert their power and dictate strict management plans for how chickens are raised.

For one, in order to be considered for a contract, growers must build facilities needed to raise broilers. These houses often cost up to $300,000 each, and most integrators require a grower to have at least a few houses before signing a contract.

So from the get-go, poultry growers are saddled with substantial debt. Most contracts last for the duration of just one flock (around six weeks), often with no commitment on the quantity of birds the integrator will purchase. Contracts are designed so that growers can be dropped with little warning, leaving them with towering debt and no place to sell their birds. What’s worse, growers are often not allowed to consult with lawyers or business associates before signing a contract, and face a secretive and intimidating process, with little say over the prices they will receive.

For us eaters who want to vote with our forks, corporate power also squeezes alternative forms of poultry production. In the drive toward consolidation, independent slaughterhouses have been forced to close, leaving many independent farmers high and dry for getting their products to your plate. And because they own the slaughtering and processing plants, corporate poultry giants can dominate the market, often unwilling to handle products like organic eggs or pastured poultry. In many states, efforts are underway to allow farmers to do on-farm slaughtering, processing and sale of their livestock. But rebuilding this infrastructure will be a slow process, and it will need the support of eaters!

People Power: What Eaters Can Do

It’s essential that we eaters not only clamor for better alternatives that support organic and sustainable farmers, but also speak up in support of poultry farmers caught in an unfair system.

Saddled with debt and holding so little power, poultry growers have been reluctant to speak out against corporate abuses. When the federal government began investigating the poultry industry in 2010, it was very difficult to find farmers who would testify despite very real threats of retaliation. We’re very lucky to be able to share the stories of three brave Farmer Hero families who have spoken out about their experiences.

The kicker is that we have the tools before us to protect farmers—the very first step to build a better, healthier, more sustainable poultry industry. A USDA agency called the Grain, Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) is charged with ensuring fair and competitive markets for meat and cereal growers. GIPSA has historically not had authority over the poultry industry, but Congress moved to remedy that in the 2008 Farm Bill. In 2012, USDA issued a rule outlining how it would carry out its expanded mission to protect poultry farmers. This represented a huge victory for thousands of poultry farmers. But corporate lobbyists quickly responded with well-funded efforts to repeal the rule. More recently, they succeeded in getting Congress to remove USDA’s authority to enforce the GIPSA rule.

The GIPSA rule’s future remains uncertain, so stay tuned for upcoming opportunities to support our poultry farmers and lay the groundwork for a better system! In the meantime, vote with your fork! Speak up when you’re choosing poultry products at stores or restaurants. If they don’t offer the kind of products you’re looking for, ask them to! Tell them you’re concerned about the conditions poultry farmers are forced to endure, and that your store/restaurants needs to ask for a better system.

Watch this video about Carole Morison, the contract poultry grower in the video above, talking about her switch to raising chickens outside the industrial contract poultry system:

Further Reading

As Farm Aid President Willie Nelson has said, “Our food system belongs in the hands of many family farmers, not under the control of a handful of corporations.” Visit this page for more facts and information on the effect corporate concentration has on farmers.