John Cardwell’s path has taken many twists and turns, but the road has always followed a deep love for his home and community in Tipton County, Indiana.

For the last 10 years, John and his wife Nancy have managed a conventional corn and soybean operation, on land he grew up farming and that has been in his family for seven generations. John has recently experienced health issues and works with his neighbor and long-time friend Jeff Harlow, who does the hands-on farming today. “Our farms have been side-by-side going back to the middle of the 19th century.” On the farm they’ve expanded their rotation to include winter cover crops over the last three years. “The cover crop is designed to retain more water, recapture nutrients, and keep the soil healthier,” John explains.

To us, John is a farmer hero not just because of how he’s adopting growing methods to keep his soil healthy for future generations, but also for his decades of policy and advocacy work on an array of issues to help his fellow Hoosiers, as people in Indiana are known. Farm Aid came to know John in the midst of the 1980s Farm Crisis, when he worked at the Citizens Action Coalition (CAC) during one of the most pivotal moments in American history.

He describes the work it took to help farmers during that time, when he started the Indiana Rural Organizing Project at CAC with the help of farmers like Susan and Phil Bright, who also worked with Farm Aid. “We spent a lot of time getting farmers to spill their shoeboxes filled with receipts onto the kitchen table to figure out their finances. We’d sit down with a clunky computer to show them how awful the loan they had been pressured into taking out truly was.”

“By the time Farm Aid started in 1985,we were fighting foreclosure battles all over the state with a team of highly trained volunteers,” he says. “I wrote a piece of legislation to create a farm legal counseling and debt mediation agency. In 1988, the Indiana Farm Counseling and Debt Mediation Act became law. The program was highly successful. It kept more than 1,500 farmers a year from bankruptcy. It ran on a surprisingly tight budget of $250,000-300,000 a year.”

John has a special fondness for Farm Aid founder John Mellencamp. “John’s one of the guys out there – in addition to being a Hoosier and sticking to our state and still living here – with coherent and specific things to say about protecting farmers and rural communities.”

The CAC rural organizing project and the farm counseling program conducted farm law seminars around the state to create teams of farmers and attorneys with a working knowledge of farm lending laws and borrower rights. The work that John and others like him did across the countryside laid the foundation for Farm Aid’s Farmer Resource Network and Farm Advocate Link, which house resources and advisors for farmers across the country. As John states, “You don’t have to spend tons of money to have a service in place that works for farmers through smart, relevant advice on their rights, legal obligations, and money management.”

Unfortunately, in 2005 Indiana Governor Mitch Daniels ended funding for the program. Similar cuts to crucial farm services have occurred in other states too, as the sharp pains of the farm crisis have faded from the country’s memory. Farm Aid is working to rebuild the farm counseling and services infrastructure – an uphill battle that will take a new generation of local leaders like John.

“Much of the organizing that was done in the 80s and 90s has faded away in Indiana,” John acknowledges “I’m 66 now. Where do we find the next generation of leaders?”

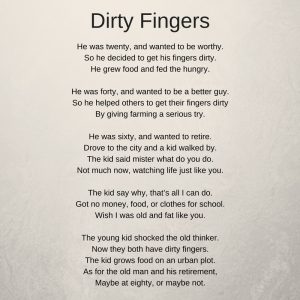

John is a giant in circles that deal with another issue facing Indiana: an aging population and long-term care in rural communities. His work during the farm crisis introduced him to a number of seniors and farmers who acquired disabilities from accidents. “At farm meetings,” he chuckles, “there’s a running joke about seeing how many people still have ten fingers.”

“One of the unstated crises in rural communities is elder care,” John asserts. “When I was a kid, we had a traditional extended family with three generations in one household. In 1960, my grandmother suddenly developed a dementia. I saw that just tear my family apart. It permanently harmed my dad’s health.”

John has been lucky to meet farmers across the globe who point to a different way. “The people I met in rural Nigeria who built the yam mounds and worked with the goats were in their 30’s and 40’s,” he recalls. “But they were advised by older people on all the subtleties of raising the crops and keeping the village healthy. It reminded me of my farming community I grew up in. But that was disappearing.”

I’m 66 now. Where do we find the next generation of leaders?

John chaired what became the Indiana Home Care Task Force, a broad coalition of organizations and leaders concerned about elder care in the state. “Seniors are the people with the accumulated cultural knowledge of those communities.” As families move their loved ones into nursing homes, he notes “there’s a hole in that community.”

John connects these kinds of frays in the social fabric of rural communities to the larger story of local economies left behind as corporate consolidation took hold across key industries in the state.

“Indiana is still one of the top manufacturing states in the country, but it’s nothing like it was,” he shares. “This place used to be full of auto plants and steel mills where farmers worked for supplemental income.” That income, combined with federal farm policies from the 1940s and 50s, “allowed small and medium farmers to prosper. But consolidation across industry and agriculture means people are having an increasingly tough time finding income.”

The development of large industrial animal operations, or factory farms, is a related concern.

“Factory farms suck,” John says bluntly, in a muted anger that draws from personal experience. “Less than a mile and a half from our farm, three factory hog farms have been put in with a capacity of 24,000 head. That’s a lot of pig poop to manage.” John struggles with chronic respiratory issues. He says, “You just don’t want to smell it. Apart from that are all the water and air pollution issues, disease potential, public health issues. I’m not buying that they can consistently manage all the problems produced by aggregating that many animals in a very small space.”

Photo: Josh Marshall / Farm Indiana

He is increasingly cynical about political leaders embracing “factory farm agriculture,” especially because of its ripple effects on independent farmers. “Corporate agriculture can use factory farms to suppress the price farmers get paid,” John notes. “That runs contrary to a farm economy that contributes to people wanting to come back to rural areas.”

And while there are places in rural communities where it would be blasphemous to say so he notes, “There is a group of conventional farmers out there who see new farming techniques as a good thing because, like myself, they’re worried about where the next generation of farmers is coming from.”

Like many parts of the country, Indiana has seen most of the new energy in food and agriculture gravitate to alternative systems like organic production, local and regional food system development and even urban farms. At a time when the country can feel divided along rural and urban lines, John feels that split is actually softening in his part of the state as these new approaches grow.

“We need to get America back on track with a healthy environment and healthy foods. Doing that in a way where urban communities can participate is wise,” he says. “We have farmers’ markets all over the area and a winter farmers’ market in downtown Indy. There’s a growing organic and urban farming movement. You can find people raising chickens and micro-crops. Increasingly, conventional farms are diversifying into new ventures. That didn’t exist 10 years ago.”

Photo: Josh Marshall / Farm Indiana

He sees wind energy as another opportunity to diversify farm income, rejuvenate rural economies and stave off the pressures of development. John notes that wind energy can also put farmers in a more stable financial position, where they can afford to look into alternatives like organic and non-GMO markets, or to employ more ecologically based weed management programs.

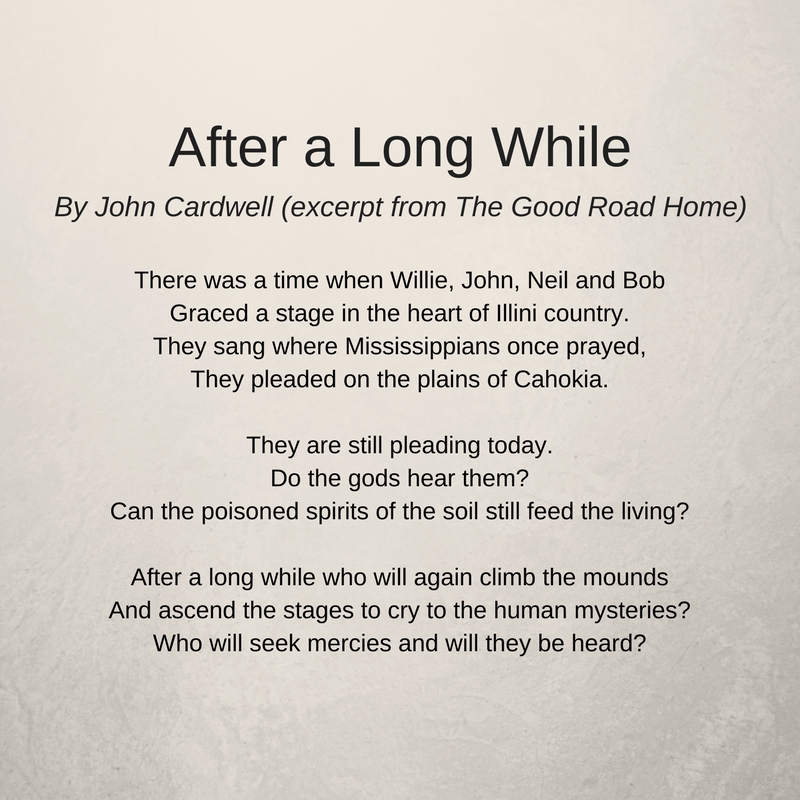

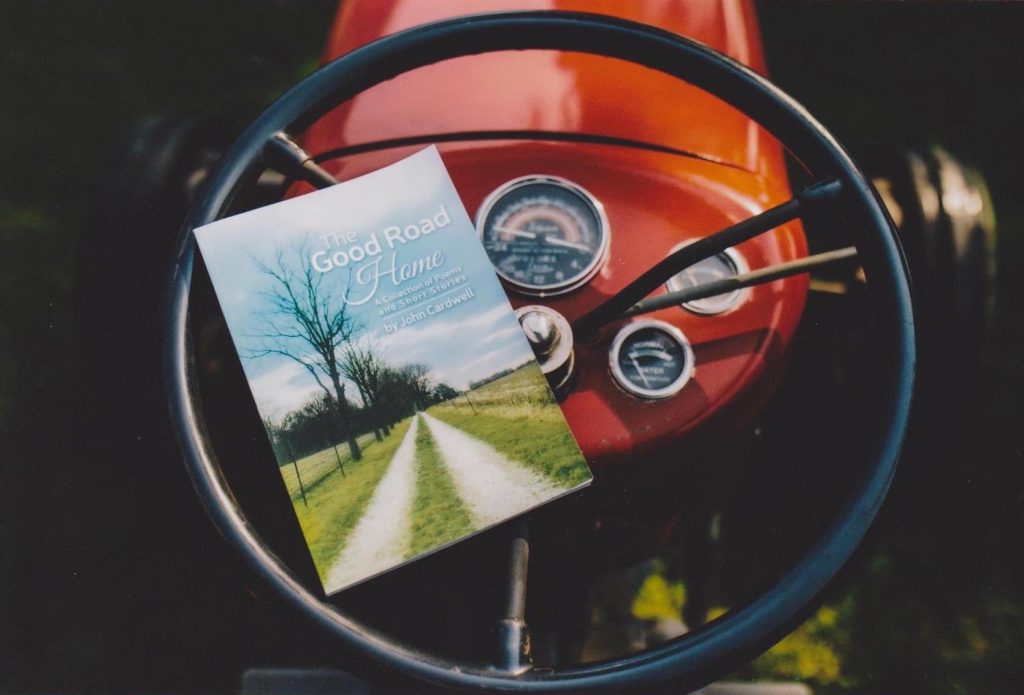

These are some of the things John meditates on in his new book, The Good Road Home, which he calls a personal adventure that focuses on the part of Indiana he calls home. “It starts with a geological history of why the land is the way it is,” John explains. “And you come on up through the generations and bring it into contemporary times. It tries to create a unified story through poetry and prose.”

These are some of the things John meditates on in his new book, The Good Road Home, which he calls a personal adventure that focuses on the part of Indiana he calls home. “It starts with a geological history of why the land is the way it is,” John explains. “And you come on up through the generations and bring it into contemporary times. It tries to create a unified story through poetry and prose.”

The short story Evening Harvest, for example, asks larger questions about where farming is today. “If we can’t sustain where it’s going for seven billion people on the planet, we’ve got a real problem.”

“Looking to the future, you want more people coming into agriculture,” John offers. Rooted first and foremost in his life on the land, The Good Road Home shares his hard-earned insights on how we may get there, and precisely what it is about family farm agriculture that is worth saving.