North Carolina is notable for its history of tobacco production and its forward-thinking shift out of the tobacco economy over the past decade. Historically a lifeline for small farmers across the region, dramatic changes in the tobacco industry forced farmers to develop new sources of income. The result has been a truly revitalized farm economy in North Carolina, built on direct markets, value-added production, organic production and diversified farming systems.

One benefit of moving the Farm Aid concert around the country each year is getting to know the farmers in a particular state or region. This year, we are thrilled to be celebrating North Carolina’s innovative family farmers and the agricultural renaissance they are leading.

What’s so special about North Carolina and the family farmers who steward its lands?

To answer that question, we have to flip back through the pages of history to colonial America, when a plant named Nicotiana tabacum – tobacco – reigned supreme. You could even say that tobacco put North Carolina on the map. But it’s the work of North Carolina’s tobacco farmers and their transition to new crops and enterprises in the post-tobacco era that really makes the Tar Heel State shine.

From Colonial Cash Crop…

Colonial times brought stiff competition between Virginia’s tobacco growers and those of an emerging colony to the south, the “Lords Proprietors of Carolina,” to feed Europe’s growing appetite for the crop. So valuable was tobacco that in the late 17th century it actually served as currency in Carolina (Fun fact: In 1672, the price for rum in Carolina was set at 25 pounds of good tobacco!). In 1776, at the birth of America’s independence, England launched a “Tobacco War” against Virginia, destroying millions of pounds of tobacco and opening up the market for North Carolina tobacco farmers to become the top tobacco producers of the fledging nation.

Fun fact: In 1672, the price for rum in Carolina was set at 25 pounds of good tobacco.

By the mid-1800s, North Carolina’s tobacco economy took off. In 1839, a slave in Caswell County named Stephen accidentally cured tobacco with fire, creating the state’s signature yellow-leaved “Brightleaf” (or flue-cured) tobacco that became wildly popular. This flue-cured tobacco could thrive in the poorer soils of eastern North Carolina, allowing once-struggling farms to be financially viable. Tobacco factories started opening across the state – first in Durham and then in other towns that would become North Carolina’s largest cities, housing the world’s largest tobacco companies.

Collection of ads from Durham Tobacco by Alexisrael licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0.

For well over a century, North Carolina’s farm economy boomed as it became the leading tobacco producer in the U.S. While the Great Depression brought hard times to all farmers, tobacco was one of the protected crops supported in the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1939 – the very first Farm Bill – through production quotas, acreage allotments and price support loans set by the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA). Not only did these policies support incomes for farmers and buffer prices for consumers, in North Carolina the policies meant thousands of small tobacco farms would survive and thrive through the many ups and downs of the market.

…to 20th Century Crash

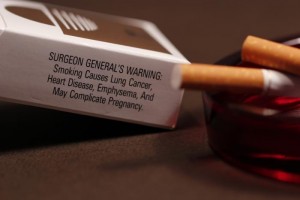

In 1964, the U.S. Surgeon General issued a historic warning that linked tobacco to lung cancer. The news rocked the American public and the tobacco economy was never the same. Over time, the domestic market for tobacco plummeted, while foreign demand for high-quality U.S. tobacco dropped and tobacco manufacturing moved overseas. U.S. tobacco farmers started going out of business.

Still, by 1997 nearly 90,000 U.S. farmers were growing $3.2 billion worth of tobacco, mostly on small, family-operated farms. Twelve-thousand of those farmers were in North Carolina, where they earned more than $1.2 billion that year. But the tobacco economy continued to decline. In the five years between the 2002 and 2007 Census of Agriculture, the number of U.S. tobacco farmers declined by over 70 percent, from 57,000 to a little over 16,000 farmers.

In 1998, the Tobacco Master Settlement Agreement (MSA) settled disputes between the attorneys general of 46 states and the four largest tobacco companies, with enormous payments made by the tobacco companies to compensate for tobacco-related illnesses and medical costs. Just a few years later, the federal government decided to end the support policies that had bolstered the tobacco economy since 1939. The Fair and Equitable Tobacco Reform Act passed in October 2004 as part of a larger jobs bill and its main component was the Tobacco Transition Payment Program (known as the “Tobacco Buyout”), which established $9.6 billion in payments (funded by assessments on tobacco companies) to tobacco growers and quota-owners over a 10-year period, in order to buffer the dramatic shock of ending the support policies.

Shadows of the Tobacco Economy

Just as important as tobacco’s economic decline are important social and environmental issues that have long plagued the industry. Tobacco is an incredibly labor-intensive crop and as such, shares a shameful history with the slave economy that powered the South through the Civil War. Today, larger growers in particular have needed hired labor to raise and harvest the crop. Labor standards in the industry have been criticized for decades and several efforts – including the groundbreaking work of a Farm Aid partner, the Farm Labor Organizing Committee – have organized tobacco workers to advance their rights amid inhumane and unsafe conditions. As financial margins continue to squeeze farmers, the need for fair labor conditions in tobacco fields weighs heavy on the conscience of the industry.

Tobacco is also a chemical-intensive crop that requires several applications of insecticides, weed-killers and other pesticides. Both ground and aerial applications of these chemicals have exposed workers, neighbors, the soil and waterways to toxic pesticide drift and runoff. Alternative methods for tobacco production are few and far between, though organic tobacco production has advanced in some areas, including in North Carolina. Still, the environmental impact of tobacco is by-and-large an unanswered problem that was just one more pressure driving individual tobacco farmers to find another livelihood.

Transition Times

So what happened to family tobacco farmers?

Times of great transition are generally not times of great risk-taking. When income is decreasing and future prospects are uncertain, people tend to hunker down and wait to see what will happen. But in order for farmers to transition out of tobacco – something they relied upon for centuries – they needed to forge a risky path into the unknown.

Easier said than done, of course. With over 80 percent of North Carolina’s buyout recipients collecting less than $5,000 annually, most tobacco growers weren’t in a position to gamble on new farm ventures.

But in North Carolina, there was a dedicated effort led by farmers, community-based organizations and the state government to forge a new agricultural future. Organizations like Farm Aid’s long-term partnerRAFI-USA issued programs like the Tobacco Communities Reinvestment Fund, which worked with and financially assisted tobacco growers interested in opening new enterprises. The results speak for themselves. In 2011, RAFI provided nearly $2 million in cost-share grants to 180 innovative farms in North Carolina. A study by the University of North Carolina at Greensboro found that each grant (averaging $10,000) creates 11 new jobs within a year, and each dollar invested creates $205 in economic impact annually in North Carolina.

RAFI’s work is reflective of broader transition efforts in the state. The General Assembly created the NC Tobacco Trust Fund Commission in 2000 to soften the financial impact to farmers caused by tobacco’s sharp decline. Since 2002, the NCTTF has awarded over 200 grants to public and nonprofit agencies with a goal of strengthening rural and tobacco-dependent economies in the state.

A Bright Outlook

Colorful veggies at the Moore Square Farmers Market in Downtown Raleigh, NC. Photo by flickr user alli-son courtesy of Creative Commons.

What has resulted is a completely reinvigorated agricultural economy built around promising new markets, sustainable production methods and products, and thriving demand for family farm food among restaurants and wholesalers in the state. Former tobacco growers are now starting farmers markets, establishing their own creameries, fostering prawn cooperatives, forging new farm-to-table establishments in urban centers and much more. What could have been the death knell of the state’s farm economy actually seeded North Carolina’s robust farm economy centered around diverse agriculture and deepened connections with eaters.

Today, there are only 1,046 tobacco farms in North Carolina.[1] 2014 marks the final year of the Tobacco Buyout and while it is expected that many more tobacco growers will exit the market in the following years, the future of North Carolina agriculture is bright due to forward-thinking innovations from family farmers and those that support them.

Sources

1. NASS US Department of Agriculture. (2014) Census of Agriculture Table 51: Selected Characteristics of Farms by North American Industry Classification System: 2012.