Ithaca, N.Y.

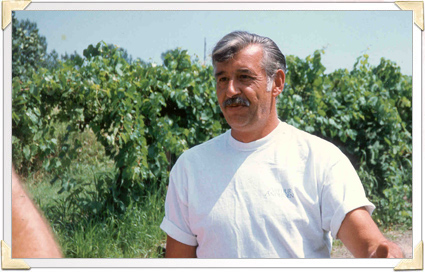

We spoke recently with Kenneth Barber, whose Stone Arch Farm, located 18 miles northwest of Ithaca in the Finger Lakes region of New York, is a highly diversified, low-input, all-natural operation — “beyond organics,” as Ken likes to say. The farm produces grapes, peaches, cherries, pastured-raised chickens and eggs, and includes an on-farm bakery, a woodshop, and much more. The family sells both directly to customers at the farm itself and two days a week at the Union Square Farmers’ Market in Manhattan.

Q: What’s new on the farm?

A: We experimented a bit with an on-farm farmers’ market this year, and next year we’ll be operating our own farmers’ market, seven days a week. We’re in a rural area, and it’s a 30-mile round trip to the grocery store for folks around here. So we think our own daily farmers’ market makes good sense.

We’re trying a new concept for it: cells. We’ll have seven farmers in a cell, and each cell will be responsible for running the whole market one day a week. This will allow time for a small farmer to farm and have time to build a following for his product. We’ll keep the vendor fees very low. One old joke I’ve heard is that the only way to make money in farming is to farm farmers, but that’s not what we’ll be doing. We’ll be working together to keep each other going.

We’ll also be trying some other things. We live in a tourist and camping area here in the Finger Lakes, so we’re going to add a miniature golf course, an archery range, and a campground in coordination with the whole thing. Sort of going back to the things we used to enjoy when I was young. We’ll also have a story-teller to spin local lore, and maybe even a blacksmith. Nearby is a national forest with horse trails.

Q: Some years ago you called the Farm Aid Hotline. What prompted that decision, and what was the result?

A: I’m a past president of the New York Wine Growers, and [in the 1980s] our industry was outsourced, and no one was prepared. I saw people lose their farms, their families, and their lives, including suicides. For us it really began in 1976, when we still had a very large vineyard, around 1,100 acres. We were selling wholesale, and had whole families living and working on the farm. But after that we lost the entire market, and people were the victims of outsourcing and the “bigger is better” mentality. People were misled by conglomerates, told to plant this or that variety of grape, and many went completely broke.

I called the Farm Aid Hotline in 1986, and Farm Aid referred me to New York Farm Net, who helped me out. From there I filed Chapter 12 and saved a substantial portion of the farm. Even today I wouldn’t say that I’m fully, totally recovered, and with land prices sky-rocketing in our area I could sell my land to developers and be a millionaire. But I’m not willing to sell and break up this farm into small pieces for development. Once it’s gone [to developers], it’s gone. But I did sell 60 acres to the national forest, which will be there for my grandchildren.

Q: How long has the farm been in the family?

A: My dad farmed here beginning in 1957, so this year our farm is 50 years old. My maternal grandfather farmed in New Jersey, and my paternal grandfather farmed in Delaware. Before that we were farmers in Europe.

My grandchildren are here all the time. I learned from my grandparents, and I think the generational thing is how we learn. We’re losing out when people don’t live with or near their families. Ideas come out through all that exchange.

Q: Do you enjoy traveling each week from the farm to the Big Apple for the Union Square Farmers Market?

A: It’s kind of great, actually. I love going down there. It goes back to the idea of exchange. It’s the community that makes a farmers’ market great. At Union Square it’s an exchange of ideas, of cultures, and we all benefit from that understanding. And I get to dispel myths, both ways, urban and rural. In some ways it’s almost a refuge going to New York every week. I have diabetes and I check my sugar level regularly, and, believe it or not, my sugar level is always higher when I’m at the farm. On the farm, you have one problem, and before you can solve it, you have another problem. Also, I like the five and a half hour drive to and from the market, because it gives me a chance to think, slow down, ponder ideas. Everybody needs that, that meditative moment. People don’t take the time they actually need for that.

Q: Back on the farm, what’s an average day like?

A: There’s never an average day on the farm. Every day is different. But of course we have our rural community here, too. We have local heroes you’ll never see on the sports page or on the national news. But they’ve pulled people up the ladder with them by sharing ideas. Nowadays, some people get up to the top of the ladder and then kick the ladder away.

Like in most places, we’re losing farmers, and when you lose numbers of farmers, you also lose your infrastructure, your parts dealers, etc. Today, to get parts for my tractor, it’s a full day’s trip. When the farm community crumbles, your costs go up, and everyone loses.

Q: At 65 years old, do you have any advice for beginning farmers?

A: Stay as diverse as you can. Don’t put all your eggs in one basket. You do not have to borrow a lot of money. I borrow no money whatsoever. I have no credit cards, and I operate strictly on a cash basis. It can be done.

Be realistic. Take time to reflect and pick out your true values. If what you want is to drive a Mercedes, get a job on Wall Street, make a lot of money, and then kick the ladder away. But don’t be a farmer.

Be as flexible as you can possibly be. Once you’re owned, you’re in trouble. Do not go into debt any more than necessary. I’m 65, and I’ve got a hundred ideas! I wish I was 25!

Q: What’s one new idea?

A: The real opportunity right now is with individual farmers producing their own energy. We need to come up with a farm policy that emphasizes farm-produced energy. The Germans are already doing this, with technological and engineering help from their government. We need to think big, but the production end should remain small. The major developers will destroy all our farmers. We can have a rural renaissance in this country if empower the individual, not big business. The political climate could not be better for this kind of proposal. It’s a great way to get dollars into rural pockets, and by spreading out the production of energy, we also protect national security. It’s a win-win for all, except big corporations!

Date: 12/18/2007