The following 101, on buying a whole pig, comes from HOMEGROWN contributor and Portland Meat Collective founder Camas Davis. For a taste of what PMC teaches, keep reading. (Going whole hog is a great place to start.) Thanks so much, Camas.

Buying a Whole Pig 101

So you want to fill your freezer with pork. And you want to do so by buying a whole, or maybe a half, pig directly from a farm. You want someone to kill it and gut it and clean it. Then you want to butcher it yourself. And maybe you want to make your own bacon and sausages and hams.

OK, OK, let’s not get ahead of ourselves. Let’s say you aren’t ready for the bacon and the ham parts or the butchering part quite yet. No worries. A good first step is buying a whole pig directly from a farmer you trust, getting it slaughtered, and then having someone cut and wrap it for you. We can deal with all of the rest later.

Step 1: Get A Freezer

Unless you’re buying a whole pig that you plan to plow through in a single event—a pig roast block party, for example—you’re probably buying this pig for you and your loved ones to eat over time. That means you’ll need a freezer with enough room for about 200 to 300 pounds of meat and bone. That’s not a regular freezer. That’s a big freezer—a deep freeze, like your grandma probably had or still has, because that generation was good at storing food for long periods of time. I got my first freezer at an estate sale: the best place, other than maybe Craigslist, to find one. No need to buy them new. There are plenty of gently used ones roaming the universe.

Step 2: Locate A Farmer

Second, you’re going to need to find a farmer who will sell you a whole or a half pig. In all states, if a livestock producer wants to sell meat, he or she must have the livestock slaughtered and processed at a USDA-inspected facility. Then that meat must be wrapped and sold at butcher shops or meat counters.

USDA Photo by Lance Cheung

In some states, though, it’s OK for livestock producers to sell “live” animals, which the customers, as the new owners, can then have processed at a “custom-exempt” state-licensed facility. This is how meat shares and meat CSAs are possible in many states. You become the owner of a live animal (i.e., your name gets tagged on the animal at the time of slaughter) and then you either hire someone to cut and wrap the animal for you or you do it yourself. Some areas of the country have a larger percentage of farmers who will sell whole or half animals directly to consumers. Some states won’t even allow farmers to do that. So first, you need to find out if it’s possible. To do so:

Contact your state department of agriculture.

Find out if custom-exempt livestock sale and processing is allowed in your state. You can find every state department of ag listed on this page created by The National Association of State Departments of Agriculture.

You can also ask farmers at your local farmers market.

If live animal purchasing is allowed in your state, farmers are probably selling meat this way. You can find your local farmers market or for farmers who will sell directly to you using resources on our Find Good Food from Local Family Farmers page.

Ask questions.

Once you find a farmer who will sell you a live animal, you want to get as much information as you can—depending on how far you want to dig into the pig’s past, that is. Me, I like to go deep. No, you don’t have to get all Portlandia and ask if the pig had a best friend in the farmyard, but some questions I like to ask include:

- How does the farmer raise his pigs? Are they pasture raised for their whole lives or do they spend a lot of time in a barn or a farrowing pen? How much do they move around? How are the mamas treated? What are they fed? (Kitchen scraps don’t necessarily make for a good-tasting pig.) GMO or organic or … ? Wheat? Barley? Peas? Corn? Soy? How do you feel about the use of corn and soy as animal feed? I like evidence that my farmers have really studied their feed in order to raise happy pigs that will have a nice fat-to-meat ratio. In talking to the farmer and asking questions, you’ll become more educated yourself. It’s up to you to decide what your standards are. Over the years, mine have become pretty strict.

- How old are the pigs when they’re slaughtered? Personally, I prefer older, bigger pigs that have more fat on them so that I can make good bacon, sausages, hams, cured products, etc. But if you want only fresh cuts, or if you’re having a pig roast for 25 people (as opposed to, say, 100), you might want a pig that’s six to nine months old and around 175 to 225 pounds.

- What’s the price per pound? A good range is typically $2.50 to $5.50 per pound, depending on breed, feed, and other production details. Keep in mind that weight includes not just meat but also bones, cartilage, skin, and other bits, all of which are tasty and useable.

- Are the animals slaughtered on the farm (preferable) or are they transferred somewhere else to be slaughtered? Will the farmer help arrange slaughter and processing?

Step 3: Pick A Pig

Once you’ve chosen a farm you want to buy from, you need to decide whether you want a whole pig for yourself or if you want to go in on a pig with friends. Typically farmers don’t want to sell one animal to more than two to four people; otherwise, it starts to look like they’re a meat reseller. With pigs, I usually split one pig between two people or two families. It’s easier to divvy up that way. You can also decide to buy only one side of pork. This means the pig would be split in half lengthwise, down the backbone. The same cuts exist on both sides.

Step 4: Set A Slaughter Date

You or the farmer needs to decide when and where the animal will be slaughtered. The farmer typically will arrange this for you. Be patient. Sometimes it can take weeks, or even months, for a farmer to get a date confirmed from his or her slaughterhouse. In addition to paying the farmer for the animal, you’ll either need to reimburse him for the slaughter, or you’ll pay the slaughterhouse directly.

Step 5: Butcher That Pig

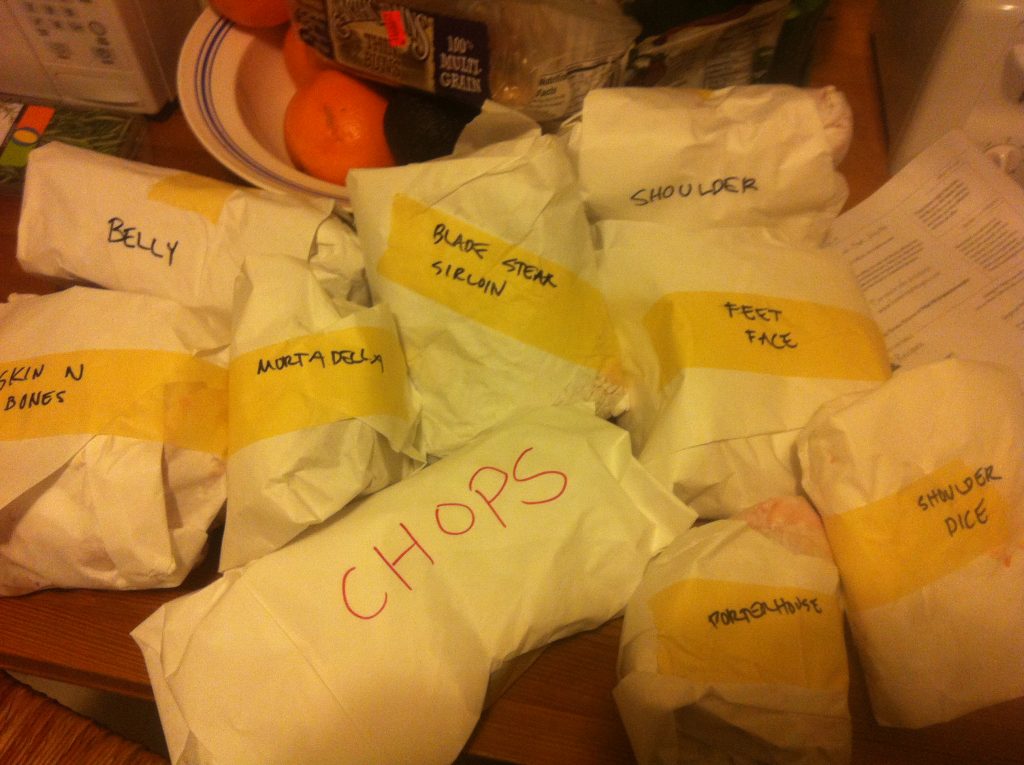

Photo by Becky Berry (CC BY-ND 2.0)

Next you need to decide whether you’re going to do the butchering yourself or if you’ll hire someone else to do it. If you want to hire someone, most “custom-exempt” slaughterhouses also can handle the butchery for you. They’ll charge you for cutting and wrapping; depending on how complex or not the cuts are, that fee usually ranges from 30 to 95 cents per pound. The butcher likely will have a standard “cut sheet” that tells you what cuts you’ll get. If you stray from that cut sheet, you may pay a little more, but it could be worth it. You can choose whether you want to keep certain parts, such as the skin, bones, head, organs, and trotters. My philosophy is that if you pay for all of the pig, you should get all of the pig—and you should learn how to use all of the pig. If you’re going to buy a whole pig, educate yourself on how to use it up, as well as on the different ways it can be cut up.

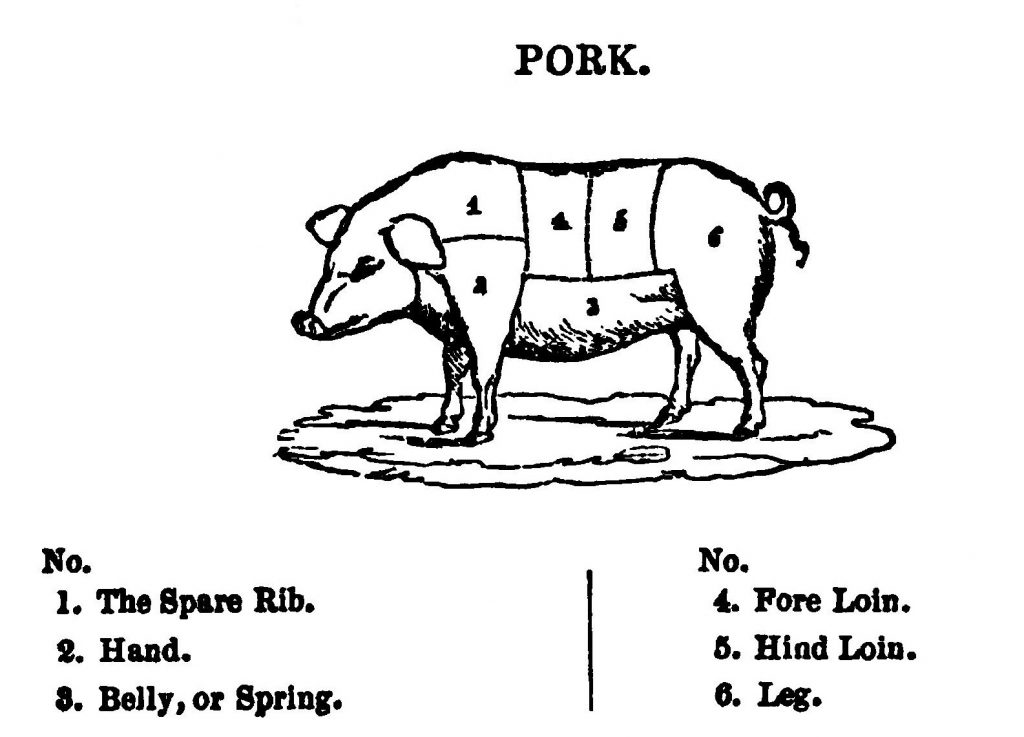

Below is a pretty standard method for cutting up and splitting a whole pig:

- Pork chops. Each side of the pig has between 15 and 30 chops, depending on whether you want them bone-in or boneless, thick or thin.

- Hams. You can get at least five or six smaller ham roasts or fresh hams from each back leg. These can be transformed into the salted, smoked hams we all grew up with. Some cut-and-wrap operations will make these for you, although I suggest you learn how to make them yourself!

- Shoulder roasts. Each side of a pig has a Boston butt and a picnic, which can be transformed into roasts, stew meat, or ground meat. Cut-and-wrap operations usually will split each of these into two or three smaller roasts. Or they’ll turn the picnic roast into stew meat or ground pork, which is always an option. But there are other interesting cuts in there, too, like the coppa, the brisket, and “El Secreto,” a cut that’s become popular these days and is, essentially, a delicious flap of meat embedded within the Boston butt.

- Belly. There are two bellies on a whole pig, one on each side, because the pig’s belly is always split down the middle at the time of slaughter in order to eviscerate its innards. You can ask the butcher to make bacon for you, or you can ask to receive the belly whole or cut into smaller pieces. That way, you can make your own bacon or pancetta.

- Trotters. These are the pig’s feet. You’ll get four of them, if you want them. And you do. They make amazing stock because they’re full of So. Much. Gelatin.

- Hocks. These are essentially the pig’s calves. You’ll get four of them. They’re great to brine and smoke and then use in soups, stews, and beans. You can also ask the butcher to turn the hocks into osso buco steaks.

- Bones. Ask for these, too! You can make delicious broths and stocks out of them. If you haven’t bought this book yet and discovered the health benefits of bone broth, you should.

- Ribs, two racks. You can specify whether you want the butcher to take the ribs off of the belly, which you can then use as soup bones, or whether you want the ribs cut into baby back or spare ribs (among other styles of rib).

- Skin. If the slaughterhouse is able to scald and scrape the skin to dehair it, you can get the skin wrapped, too. Skin is great to poach and incorporate into soups or sausages. I throw little rolls of skin into my soups, stews, and cassoulets. It can also be used to wrap and cover lean cuts of meat or wild game during cooking. Don’t underestimate the power and tastiness of pig skin! You can even ask to have the skin left on your roasts and pork chops.

- Leaf lard. This is the kidney fat. If you render it, you can use it to make the most amazing pie crusts.

- Fatback. If you don’t like a lot of fat on your pork chops, ask the butcher to trim off the fatback and give it to you in cubes. You can render the fatback down for lard, or you can use it to make rillettes or sausage.

- Pig head. This is my favorite part of the pig. There are so many things you can do with it: tongue tacos (AKA lengua), porchetta di testa, posole, jowl bacon (AKA guanciale), stock. Don’t throw that pig head away! Learn to use it and coax it into delicious dishes.

- Organs, AKA offal. The heart, liver, spleen, and kidneys all can be turned into delicious dishes. Consider learning to use them in your cooking.

Step 6: So You Want To Butcher A Pig Yourself

I started the Portland Meat Collective so that I could learn to butcher pigs myself. What’s a meat collective, you ask? There’s only one—so far: the Portland Meat Collective.

Photo by Becky Berry (CC BY-ND 2.0)

The PMC is a one-of-a-kind meat school and culinary resource that has changed the way citizens of Portland, Oregon, think about their food, their community, and their local economy. For each Portland Meat Collective class, local farmers sell whole animals to students, who in turn learn from local butchers and chefs how to transform those whole animals into everything from pork chops to bacon. Students go home with a lot of good meat and a lot of very rare knowledge. Chefs and butchers have the opportunity to share their art. And farmers are able to sell their animals directly to consumers who truly appreciate their humane and sustainable farming practices. The result? A growing community of informed omnivores rethinking meat consumption and production in America.

Consider taking a class at the Portland Meat Collective. Or, if you’re farther afield, start your own.

Related Videos: Butchering A Pig, In 3 Parts

Want a preview of what to expect when butchering? In the videos below, from Cooking Up a Story‘s awesome “Food.Farmer.Earth” series, Camas butchers a pig in three parts: shoulder, midsection, and leg. You can find these and more collaborations between Camas and Cooking Up a Story, as well as loads more CUAS videos, on YouTube.

How to Butcher a Pig: Shoulder

How to Butcher a Pig: Midsection

How to Butcher a Pig: Leg