Overview

The first Farm Bill was drafted in 1933, in the wake of the Great Depression and the Dust Bowl, to address the needs of America’s farmers at a time when hunger and poverty were widespread in the country. During the depths of the Depression, farmers kept producing to scrape by, but Americans had no money to buy up their goods. The environmental catastrophe of the Dust Bowl intensified the crisis. Farm prices tanked and the federal government responded by paying farmers to cut back on their production, and then buying surplus agricultural goods to provide for hundreds of thousands of hungry Americans. As a result, the first of 18 Farm Bills established a long-standing political handshake that recognized that the needs of both farmers and poor Americans were deeply intertwined.

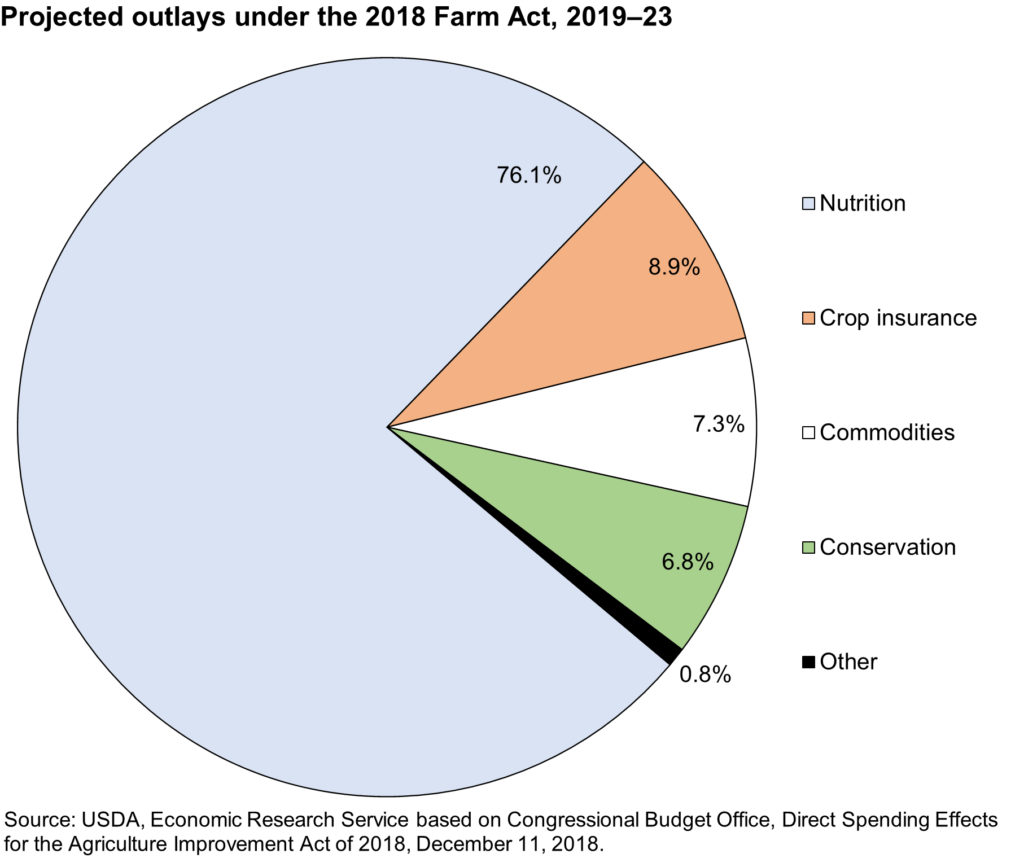

Since 1933, roughly every five years, the federal government reviews the food and farm landscape and renews this enormous omnibus bill, which we call the Farm Bill. A handful of issues usually dominate Farm Bill spending, including nutrition, crop insurance, conservation and commodities (see chart below). The remaining 1% of spending packs a potent and increasingly important punch, covering many innovative programs that are changing the landscape for farmers and eaters in the U.S., and include issues as varied as international trade, rural development, local food systems, beginning farmers, racial equity, research, forestry and more. The fate of these program hinges on 2023 Farm Bill negotiations, where programs could be cut, reduced, reshaped or expanded.

The Current Political Context

With a divided Congress, an increasingly polarized political climate, and many members of Congress intent on slashing spending to reduce the national deficit, some are skeptical that Congress will reach an agreement to pass the Farm Bill before the September 30 deadline. The 2018 Farm Bill was delayed for nearly three months, finally being signed into law on December 20, 2018. So far, members of the House and Senate Agriculture committees seem committed to passing a new Farm Bill on time. But there are significant differences in opinions about what a new Farm Bill should do.

Fiscal conservatives aim to slash spending, particularly on nutrition assistance and conservation. Meanwhile, others are focused on increasing our investment in climate-resilient agriculture—supporting farmers and ranchers to cope with and manage the impacts of climate change on their farms while also implementing sustainable agriculture methods to prevent those impacts from growing worse. This is a move Farm Aid supports, not only because it strengthens farmers, but because it strengthens all of us.

As Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack pointed out recently in a speech before the National Sustainable Agriculture Coalition (NSAC), “There’s historic money invested in this that some people want to take away. You can’t let them.”

Making a Farm Bill

Like any bureaucratic process, the road to a new Farm Bill is a long one. Both the House and Senate Agriculture Committees work on their own versions of the bill, which must be “scored” by the Congressional Budget Office with a cost estimate before reaching the floor of their respective chambers for a vote. Once each chamber of Congress records the votes to pass their version, the House and Senate then must collaborate to finalize one consolidated bill to send to the President for this signature.

Once passed and signed, the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) begins the implementation phase, interpreting the law and putting it into action. While the Farm Bill process can feel long, implementation is the real time-consuming process. Some programs of the 2018 Farm Bill are still in the process of implementation by USDA nearly five years after passage.

The Agriculture Committees never start from scratch to create a Farm Bill. Each Farm Bill has been built upon the previous one, making both minor and major changes. In theory, Congress will approve a new Farm Bill by September 30, 2023, reauthorizing programs needed by many farmers, rural communities and eaters alike, and authorizing new programs. If Congress fails to meet that deadline, they’ll vote to temporarily extend the most recent 2018 Farm Bill. Many programs will maintain funding under this temporary fix, but programs that require annual funding approval will be out of luck, and so will the farmers, eaters and communities who depend on them.

Both sides of the aisle have indicated that they aim to pass the 2023 Farm Bill on time, an especially important task to them politically as the nation heads into a presidential election year and, more importantly, a task that is crucial for the livelihoods of our country’s farmers and ranchers.

The 12 Titles of the 2018 Farm Bill

The Agricultural Improvement Act of 2018 was organized into twelve titles, but previous farm bills have contained as many as 25 titles. Below we’ll take you through each of the titles from the 2018 bill, keeping in mind that many key issues span multiple titles (e.g., you’ll find dairy and livestock in Titles I and XII, and organic agriculture in Titles III, IV, VII and X). We’ll also highlight some example programs and identify debates that are either ongoing in each farm bill cycle, or particularly of note in 2023.

Title I: Commodities

$314 Billion over 5 years, 7.3% of total

The commodities title dates to the very first farm bill in 1933, and it works to ensure that farmers growing widely-produced and traded non-perishable crops, like corn, soybeans, wheat and rice—as well as dairy and sugar and crops like wool, mohair and honey—stay afloat. The mechanisms this title uses can change according to politics, farmer need and even international markets.

For several decades after the Great Depression, this title focused on market stabilization programs, such as price supports (like price floors, which set a lower limit that the price of a good or service cannot fall below) and supply management programs (like farmer-owned grain reserves). These concepts had been implemented during the Great Depression to stabilize crop prices and prevent the prices of agricultural products from falling so low that farmers could not afford to grow their crops.

But this approach began to be dismantled in the 1970s. By the time Farm Aid began in 1985, the commodities title had morphed to deficiency payments that made up the difference for farmers when market prices fell below a set target price. As free market and free trade policies gained political steam, market stabilization was fully removed in the 1996 Farm Bill under increasing pressure to “get government out of the marketplace.”

A 12-row corn harvester transfers feed corn to a grain cart on the John N. Mills & Sons farm in Virginia. Photo: Lance Cheung, USDA.

The removal of traditional price and supply measures coincided with the opening of international markets through the North American Trade Agreement (NAFTA). A flood of goods on the market tanked farm prices and huge emergency payments were issued in response. Those emergency payments were turned into permanent “direct payments” in successive farm bills, no longer linked to market prices, but instead based the acreage and yield histories of individual farmers. As it became politically unpalatable for the government to pay farmers this way, the most recent farm bills introduced “revenue insurance” programs to support farm income. Yet these programs have been criticized for having a perverse effect—a huge amount is paid to insure revenue during high-priced years, and very little is spent out by these insurance programs to support farmers in low-priced years.

The debate

Critics and experts alike have acknowledged the profound impact that different programs in the Commodities Title have had on the structure of American agriculture. Since the 1970s, policies have rewarded or encouraged big farms to get bigger, while under-serving small and midsize farms, diversified operations, and beginning and socially disadvantaged farmers. A recent USDA report shows that the largest farms, with sales of $1 million or more, operate nearly twenty-six percent of U.S. farmland—6 percentage points more than they did just a decade ago.

Additionally, these policies encourage industrial farming practices that erode soil health and leave conventional farms particularly vulnerable to extreme weather events and market shifts. They also completely abandoned the idea of stabilizing farm prices and instead pay out huge amounts of money to respond to extremely volatile market conditions in ways that few other economic sectors endure. This remains one of the enduring political and ideological controversies of each farm bill cycle.

Key Programs

- Price Loss Coverage (PLC) & Agricultural Risk Coverage (ARC): These insurance-like commodity programs kick in when farmer revenues or crop prices are low.

- Sugar Programs: U.S. sugar producers face tough competition from tropical exporting countries. In addition to high import tariffs and quotas that protect U.S. sugar farmers (including sugar beets), sugar get its own commodity price support program.

- Dairy Promotion (Dairy “Checkoff Program”): The U.S. Government acts like an advertising agency for dairy farmers (as well as livestock producers raising beef and pork, for instance). Yup, that’s your tax dollars, working to promote farmer products!

- Dairy Margin Coverage: Dairy is a tough industry and solutions have been hard to come by. The 2018 Farm Bill authorized the new Dairy Margin Coverage (DMC) program to replace the former unsuccessful Margin Protection Program for Dairy (MPP-Dairy). The DMC program is a voluntary program that provides dairy operations with risk management coverage that pays producers when the difference (the margin) between the national price of milk and the average cost of feed falls below a certain level selected by the program participants.

Title II: Conservation

$29 Billion, 0.8% of total

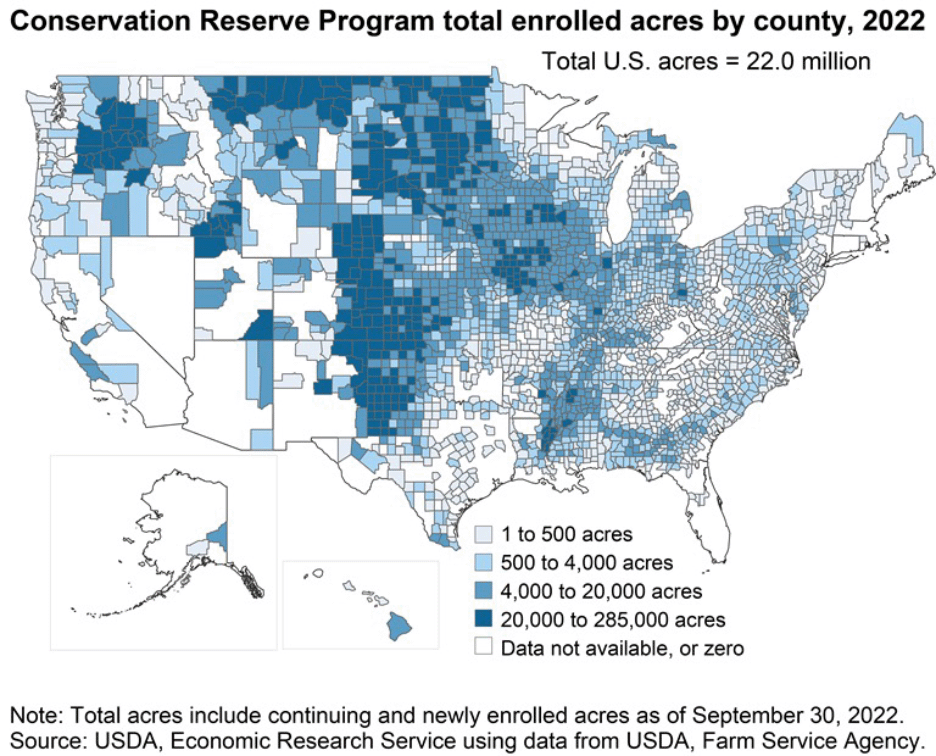

The 1985 Farm Bill created the very first Conservation Title, although previous farm bills contained programs that played a similar role in encouraging or mandating farming practices geared toward environmental protection. In fact, America’s Soil Bank program from the 1950s and 60s laid the groundwork for what would become the Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) in 1985, which established contracts with owners of highly vulnerable lands, taking that land out of production (for at least ten years) to save soil, protect our rivers, streams and drinking water, enhance biodiversity, and even to serve as a form of supply management. CRP covered about 22 million acres of environmentally sensitive land at the end of fiscal 2022, with an annual budget of roughly $1.8 billion (making it USDA’s largest single conservation program).

Other programs assist producers in adopting practices such as cover crops, conservation tillage, wetland restoration, prescribed grazing, nutrient management and tree planting to mitigate climate change and conserve land and water. USDA Conservation programs are perpetually oversubscribed, meaning more farmers are interested in participating in programs than the funding can accommodate.

The debate

Funding for Conservation Title programs has expanded in the 30+ years since its creation, and now includes land retirement programs like CRP and “working lands” programs like the Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP), which rewards farmers for establishing conservation practices on actively farmed land. This is a critical tool in the effort to mitigate climate change. But in the last two farm bills, funding for CSP has been decreased by half, restricting both farmer access to the program and its impact on climate mitigation. In addition, critics have noted that conservation programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) are working against their aim to integrate conservation into working lands by using taxpayer dollars to pay for factory farm pollution costs.

This title will see much debate in the negotiations leading up to a 2023 Farm Bill, with many pushing for this Farm Bill to be focused on climate and the essential role that farmers and ranchers play in helping us mitigate climate change through sustainable agriculture. Many in Congress and in the Administration are focused on ensuring that farmers and ranchers are recognized, supported and financially rewarded for the work they do on their farms to take carbon out of the atmosphere and put it into the soil through practices like cover crops, soil conservation, pasture-raised livestock and more.

Example Programs

- Conservation Reserve Program (CRP) pays farmers to put sensitive and highly erodible land aside via 10–15-year contracts.

- Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP) splits the cost with farmers for projects like infrastructure or production practices that help the environment.

- Conservation Stewardship Program (CSP) rewards and incentivizes farmers for farm practices that protect the environment.

Title III: Trade

$2 Billion, 0.7% of total

Title III supports international food aid programs and promotes U.S. exports abroad, in part by extending low-interest loans to countries for importing U.S. goods. Title III also helps oversee adherence to World Trade Organization (WTO) agreements and includes United States Agency for International Development (USAID) programs.

The debate

Many of the programs’ loudest supporters represent American interests: agribusiness, food processors, shipping industries and diplomacy efforts, but critics have called out programs for putting farmers overseas out of business by dumping excess U.S. agricultural goods on their markets and driving their farm prices down. A strong and growing global movement for food sovereignty exists for this reason. Food sovereignty is the right of people to healthy and culturally-appropriate food produced through ecologically sound and sustainable methods, and their right to define their own food and agriculture systems.

Example Programs

- Food for Peace (also in Title I, II and V) provides loans to countries that buy U.S. commodities, donations of U.S. commodities, and technical assistance to foreign farmers and agribusiness.

- Food for Progress donates U.S. commodities to foreign countries to incentive their governments to lower trade barriers and modernize their agricultural sectors.

Title IV: Nutrition

$326 Billion, 76% of total

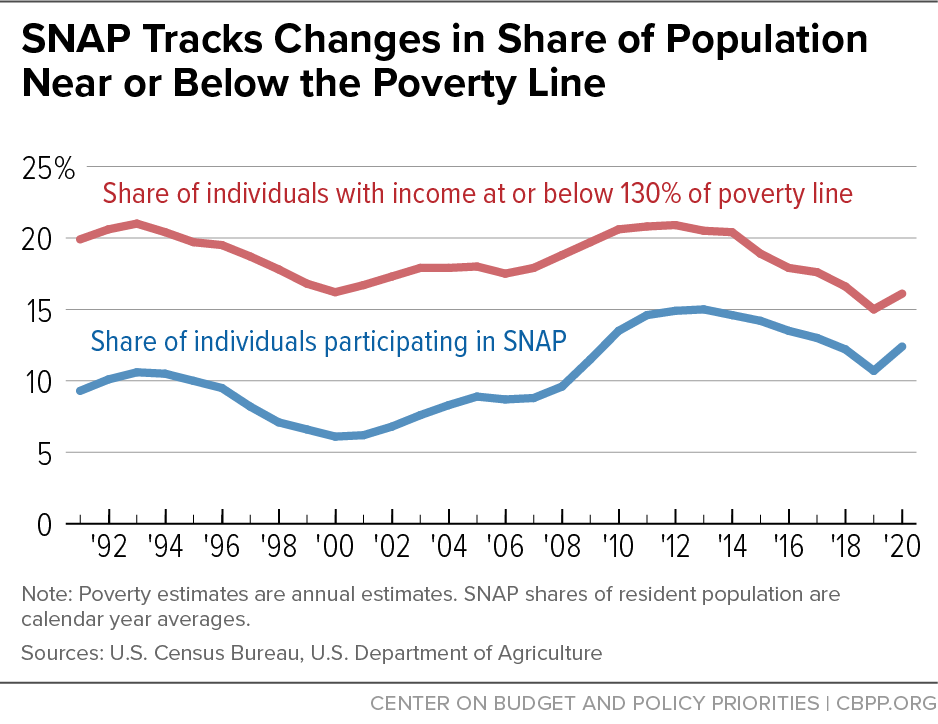

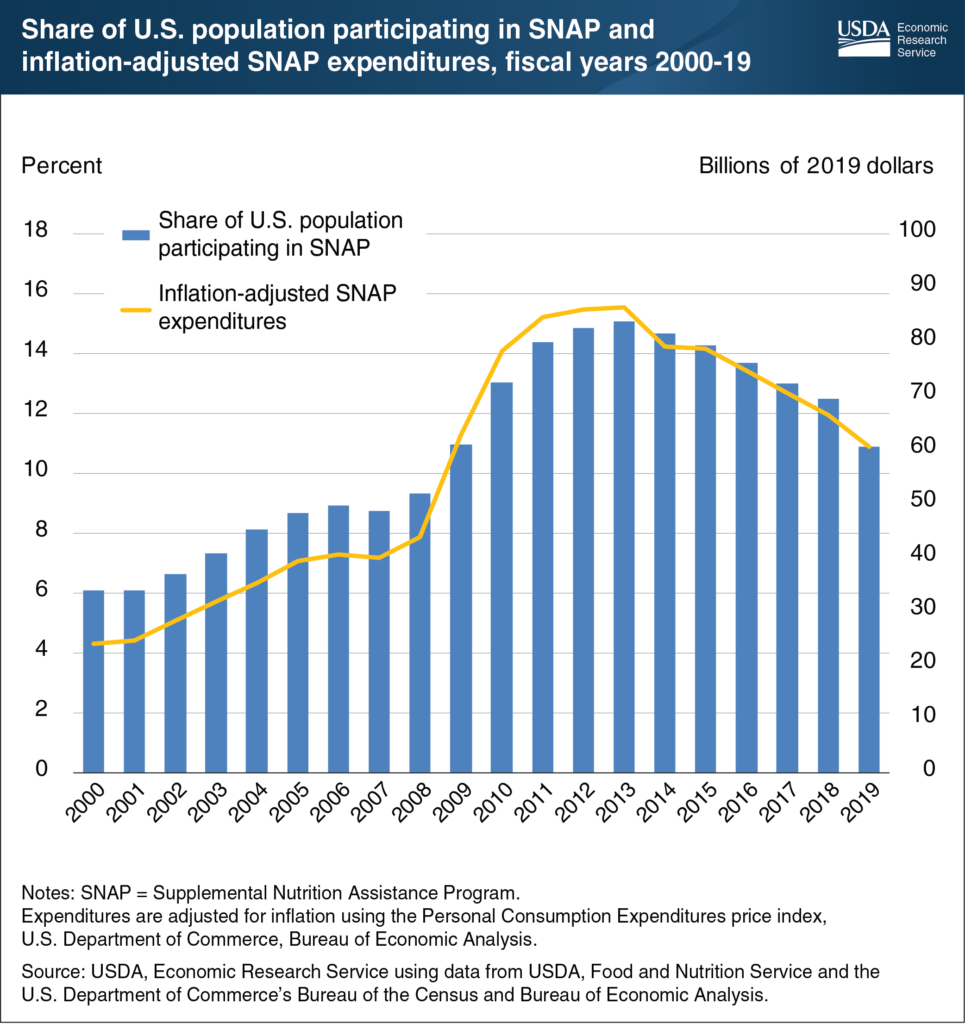

The Farm Bill’s big-ticket item is SNAP (Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program), formerly known as “food stamps,” which helps prevent hunger among the most vulnerable by assisting more than 40 million low-income people in the U.S. to afford food. This includes children, who account for 4 out of ten SNAP recipients, as well as low-income older adults (60 years and older) and people with disabilities living on fixed incomes. SNAP is simultaneously a nutrition, anti-poverty and economic stimulus program, meaning that SNAP benefits don’t just support a household’s food purchasing needs, they also augment the incomes and spending of others (such as farmers, retailers, food processors, and food distributors, as well as their employees). SNAP benefits have ripple effects for other parties, supporting the larger economy and community development. SNAP participation rates historically rise and fall with the unemployment rate.

Title IV also supports programs that promote healthy eating, education and job training for food insecure communities.

Following a decline in participation starting in 2014, SNAP participation rates and spending skyrocketed in 2020 as a result of the COVID pandemic. With the public health emergency declaration came emergency allotments to supplement regular benefits. SNAP participation rose to an average 42.5 million people per month in the second half of FY 2020 (April to September 2020), a 14-percent increase from 37.3 million in the first half (October 2019 to March 2020). Thanks to SNAP and emergency allotments (which ended in March 2023), the typical annual measure of food insecurity in 2020 during the pandemic was unchanged from the 2019 level of 10.5 percent. This stands in contrast to the Great Recession when the share of households that were food insecure rose substantially.

The debate

As a mandatory so-called “entitlement” program, fiscal conservatives consistently target SNAP for major budget cuts, and often propose stipulations like work training programs or drug testing for SNAP recipients. That is the case again in this negotiation, with those focused on budget-cutting seeking to make major funding cuts to SNAP and other nutrition programs and limit participation in programs. During negotiations for the 2014 farm bill, some even proposed removing this title altogether. Without this title, it is thought the alliance of rural and urban interests that come together to pass a farm bill each time would disperse, threatening the ability to get a farm bill passed altogether. However, as SNAP becomes more commonly utilized in rural areas, that concept is being challenged. Nationally, SNAP participation is now highest overall in rural areas (16% of households) and small towns (16% of households) compared to metro counties (13% of households).

Vegetables at a farmers market in Washington, D.C. Photo: Hakim Fobia, USDA.

Programs

- Fresh Fruit and Vegetable Program brings fresh fruit and vegetables to school children.

- Food Insecurity Nutrition Incentive incentivizes SNAP participants to purchase fruits and vegetables at farmers’ markets, supermarkets, convenience stores and retail food stores.

- Food Distribution Program on Indian Reservations: Instead of SNAP, this food distribution program distributes USDA foods to low-income households living on Indian reservations, and to Native American families residing in designated areas near reservations and in the State of Oklahoma.

- Emergency Food Assistance Program provides emergency food assistance for low-income and elderly Americans.

Title V: Credit

Title V actually earns money (from interest) with $2 million in earnings projected over the years of the 2018 Farm Bill

Since farmers put seeds in the ground months before they earn any income, credit is essential to keep farms running year-to-year, not to mention the need to finance costs like land, equipment and infrastructure needed to farm over the long-term. The Credit Title includes federal loan programs that provide farmers with the credit they need to launch, grow and sustain their farming operations.

To ensure that farmers had a steady stream of affordable, reliable credit, the Farm Credit Service was created in 1916. It later became known as the Farmers Home Administration (FmHA) and was consolidated into one of the functions of the Farm Service Agency (FSA). FSA offers direct loans and also guarantees loans provided by partner banks and farm credit institutions. Often known as the “lender of last resort,” FSA is a lifeline for farmers who are not able to receive credit through commercial lenders, and the fate of the many programs it offers is determined by the Farm Bill.

Photo: Danilo Cestonato on Unsplash

The debate

There is always a debate about the amount of funding that goes to programs in the credit title. The current Farm Service Administrator, Zach Ducheneaux, a 4th generation rancher on the Cheyenne River Sioux Reservation, has big ideas about how to change how USDA helps farmers and ranchers access credit. He often says that USDA should not be the lender of last resort, as it is often called, but instead the lender of first opportunity. A robust credit title in the next farm bill could make that a reality.

Key Programs

- Direct Operating Loans are used to purchase items such as livestock and feed, farm equipment, fuel, farm chemicals, insurance and family living expenses; to make minor improvements or repairs to buildings and fencing; and for general farm operating expenses.

- Microloans are smaller operating loans designed to meet the needs of small and beginning farmers, non-traditional and niche operations by easing some requirements and offering less paperwork.

- Direct Farm Ownership Loans are used to purchase or enlarge a farm or ranch, construct a new or improve existing farm or ranch buildings, and for soil and water conservation and protection purposes.

- Guaranteed Loans enable lenders to extend credit to family farm operators and owners who do not qualify for standard commercial loans, and help protect banks from losses if farmers struggle to pay back the loan.

- Heirs Property Relending Program: Heirs’ property issues have long been a barrier for many producers and landowners, especially Black farmers, to access USDA programs and services. The 2018 Farm Bill included provisions to help heirs’ property landowners resolve ownership issues and succession on farmland with multiple owners.

Title VI: Rural Development

The Rural Development budget in the 2018 Farm Bill was projected to have a positive return

As the percentage of America’s rural population shrinks relative to the urban population, programs in this title help grow the rural economy and ensure that “public good” services like electricity, water, credit access and business development can thrive in rural settings. This includes everything from rural business loans to water sewage systems, rural broadband, housing programs and more.

The debate

As part of an agency-wide reorganization by the Trump administration, the USDA’s undersecretary for rural development was eliminated, but the position was restored during the Biden administration. With roughly 60 million Americans living in rural counties, accounting for nearly 20 percent of the U.S. population, the role is a critical one. Supporting rural small businesses (including farms) is essential for both the rural economy and the social structure. In fact, over half of all new jobs created in deeply rural areas come from small business ventures, and most rural areas are dependent on agriculture as a large sector that drives their local economy. Rural communities are on the frontlines of climate change, and the impacts can be devastating due to a lack of investment in rural infrastructure. Two recent examples include last year’s extreme flooding in Kentucky and Hurricane Fiona in Puerto Rico. Strengthening rural infrastructure and developing rural climate solutions are crucial strategies for increasing rural resilience.

A small town in Vermont was able to secure funding for a safe, reliable drinking water supply with a USDA grant. Photo: Bob Nichols, USDA

Example Programs

- Value-Added Producer Grants help individual farmers or groups of farmers process and market new products made from raw agricultural goods (such as applesauce, jams and yogurts) or to market products that are local or produced in a notable way (e.g. organic, GMO-free, grass-fed).

- Community Facilities Direct Loan & Grant Program provides affordable funding to develop essential community facilities in rural areas, including everything from rural hospitals and fire departments to food pantries and community gardens.

Title VII: Research, Extension and Related Matters

$694 Million, 0.16% of total

Title VII invests in beginning farmers, research institutions and land-grant universities, as well as environmental, crop and farm management innovation. It covers large and small programs, grants and partnerships.

The debate

Advocates for organic, sustainable, diversified and alternative agriculture have argued that the lion’s share of farm bill research dollars support the biotech industry (e.g. GMOs), chemical-intensive agriculture and major agribusiness interests, and do not properly invest in the full diversity of American agriculture. They advocate each farm bill cycle for increased funding in this title.

Funding for public agriculture research in the U.S. has declined significantly in recent decades. Meanwhile countries like Brazil and China have increased investment in public research by as much as five times. While policymakers tend to agree that policy is crucial, when it comes to committing money to it, their enthusiasm wanes. For instance, the 2018 Farm Bill created the Agriculture Advanced Research and Development Authority (AGARDA) as a pilot program, modeled after the high-tech military research agency, the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA). Congress authorized using as much as $50 million a year on AGARDA, but the project just received its first $1 million in 2022.

Example Programs

- Beginning Farmer and Rancher Development Program provides education, outreach, mentoring, and technical and land-access assistance for the next generation of farmers and ranchers.

- Agriculture and Food Research Initiative aims to combat obesity; improve rural economies; mitigate climate vulnerabilities; train farmers; increase food production and create new sources of energy.

- Foundation for Food and Agriculture Research (FFAR) was authorized in the 2014 Farm Bill and was expanded with funds in the 2018 bill. Since then, FFAR has issued $185 million in grants for agricultural research that draws matching dollars.

aims to combat obesity; improve rural economies; mitigate climate vulnerabilities; train farmers; increase food production and create new sources of energy.

![]()

Title VIII: Forestry

$5 million, 0.001% total

This title supports healthy U.S. forests, especially on private lands through financial assistance and easements.

The debate

Forestry represents a tiny slice of the Farm Bill, but the relative importance of forests in climate change mitigation and the increasing incidence of wildfires because of climate change, could increase the size of this slice in coming Farm Bills.

A forested road in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Photo: Will Suddreth on Unsplash

Example Programs

- Healthy Forest Reserve Program offers cost-share agreements to landowners in order to enhance biodiversity, protect endangered species and advance carbon sequestration.

![]()

Title IX: Energy

$471 Million, 0.10%

This title supports on-farm renewable energy systems, including solar and wind power, as well as rural energy programs tied to biofuels. As climate change continues to increase its impact on agriculture and the world at large, there is a crucial opportunity in the 2023 Farm Bill to increase support of on-farm energy conservation and low-carbon renewable energy production.

Program Examples

- Rural Energy for America Program Energy Audit & Renewable Energy Development Assistance Grants assist rural small businesses and farmers by conducting and promoting energy audits and providing renewable energy development assistance.

- Biorefinery, Renewable Chemical, and Biobased Product Manufacturing Assistance Program: provides loans for the development of new technologies for biofuels, renewable chemicals and other products.

Title X: Horticulture

$1 Billion, 0.23%

Fruits, vegetables, nuts and nursery crops are considered “specialty crops” because they only represent 1.5% of all U.S. farmland. Though they take up relatively little space, these crops are usually “high value,” comprising 21% of total agricultural sales. Even so, producers of specialty crops get the short end of the stick under Title 1 programs, as they are not covered; so, this title is meant to address their needs.

The debate

Many of the programs in this title have helped spur local and regional food system development across the country and innovative programs that support sustainable agriculture practices or promote on-farm diversification. As with other relatively small programs in the farm bill, many of these are at risk of being cut, and yet these programs provide so many benefits compared to their relatively smaller price tag. Local and regional food systems are crucial to not just creating new markets and opportunities for farmers, but also to building food system resiliency and community food security.

A debate about this title that has long been had in the public, not necessarily in Congress, relates to the small amount of federal support for fruits and vegetables compared to the federal support for Title I’s commodities—many of which form the foundation for our cheap (because it’s so heavily subsidized) processed food-heavy diet. Fruits and vegetables, due to their lack of federal support, are often more expensive and thus out of reach for many people. This reality of this food and farm policy has been linked to obesity and other diet-related disease in the United States.

Key Programs

- Specialty Crop Block Grants help fruit, vegetable and nut producers stay competitive by providing grants to states for infrastructure, local markets and trainings for producers.

- Farmers Market and Local Food Promotion Program supports market opportunities for local farmers and businesses.

- National Organic Program governs USDA Organic standards and accredits organic certifiers.

Title XI: Crop Insurance

$38 Billion over 5 years, 8.9% of total

Congress first authorized federal crop insurance in 1938. To this day, the federal government assists producers with financial loss that results from natural disasters. Over the decades, Congress has experimented with both subsidized and mandatory crop insurance. Since 1996, farmers who accept other federal benefits (like Title I subsidies or other disaster support), are required to purchase crop insurance. Today, the government pays for approximately two-thirds of the cost of insurance; farmers and ranchers pay the remaining third.

Fourth generation farmer Chris Pawelski’s onion fields were destroyed by flooding from Hurricane Irene in 2011. Photo: USDA

The debate

The federal crop insurance program is now the most expensive program authorized in the farm bill, excluding nutrition spending, having grown by more than 70 percent in the past decade, according to USDA data. Additionally, it is a primary driver of monoculture commodity production in the United States. Record-high taxpayer subsidies benefit private insurance companies and a small number of the largest commodity farms, while most farmers are unable to access insurance at all. Farm Aid believes the 2023 Farm Bill is an opportunity to reform the farm safety net by capping wasteful crop insurance spending and investing in on-farm resilience. Additionally, the Farm Bill should strive to remove barriers in program design and implementation so that small and mid-sized, beginning, specialty crop, and organic farmers can have access to this crucial safety net program.

On the other side of the argument, some in Congress advocate that increasing crop insurance spending even more can prevent the kind of emergency outlays that have recently been made to cover losses incurred by farmers due to natural disasters, trade wars and the coronavirus pandemic. But the dramatic escalation of ad-hoc disaster relief spending (nearly $70 billion on ad-hoc disaster payments since the 2018 Farm Bill was enacted) illustrates significant shortcomings in the structure of existing farm safety net programs. It calls into question the claim that modern crop insurance is effective when it has not, in fact, it replaced the need for ad-hoc disaster payments as Congress intended. Moreover, much of this disaster assistance that has been paid out was concentrated in the hands of the largest and wealthiest farmers who arguably needed financial assistance the least, while struggling family farmers, especially farmers of color, actively engaged in farming were too often left out.

Key Programs

- Whole Farm Revenue Protection covers farms that grow a variety of crops and discounts insurance costs for more diverse farms, recognizing that crop diversity acts as an inherent risk reduction strategy.

- Disaster Assistance Programs (also under Title I) help farmers and ranchers stay afloat in the wake of severe weather and natural disasters.

- Emergency Farm Loans support farmers and ranchers hit by quarantines and natural disasters.

Title XII: Miscellaneous

$1.9 Billion, 0.45%

One last title to catch the odds and ends! From livestock research programs and maple syrup promotion, to outreach for socially disadvantaged and limited resource farmers, this title covers a wide range of agricultural programs without a home in other titles. Title XII of the 2018 Farm Bill primarily focused on livestock programs, agriculture and food defense, historically underserved producers, limited-resource producers and other miscellaneous provisions.

Key Programs

- Outreach Assistance for Socially Disadvantaged and Veteran Farmers and Ranchers: To help rectify the long history of discrimination at the USDA, this program (commonly referred to as 2501) prioritizes support for Black, Latino, Native American and other minority farmers. Recent farm bills have also added veteran farmers and women farmers into this program.

- The Commission on Farm Transitions: This commission was authorized in the 2018 farm bill to study issues surrounding the transition of agricultural operations from established farmers and ranchers to the next generation of farmers and ranchers, including access to, and availability of land and infrastructure; affordable credit; adequate risk management tools; and apprenticeship and mentorship programs.

Credits

This document incorporates work by Julie Kurtz, who helped to write and research a 101 on the Farm Bill that Farm Aid published in 2018.

Icons: Licensed under Creative Commons. Title I, Ben Davis; Title II, Symbolon; Title III, Gan Khoon Lay; Title IV, lastspark; Title V, Brand Mania; Title VI, Symbolon; Title VII, Gan Khoon Lay; Title VIII, Ron Scott; Title IX, Iconathon; Title X, Symbolon; Title XI, Hayashi Fumihiro; Title XII, Symbolon.