Hey Farm Aid,

I have heard horror stories about the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico this year. How can farmers better support our waterways?

Thanks!

James

Patterson, NY

July 2013

Water: The elixir of life. It’s a resource so precious that no living organism on Earth can survive without it, including our crops, livestock and all the food grown by our family farmers.

Whether through rainwater or groundwater, snowpack or irrigation, our entire food system depends on the availability of fresh water. With agriculture accounting for 70% of the fresh water used worldwide, the challenges of climate change, population growth, increased urbanization and industrialization, and growing energy demands place greater pressure on our finite water resources.

Now and into the future, agriculture will need to grow food with less water, employing better on-farm water management and conservation practices to do so.

Blessing or Curse

For most farmers, their relationship to water boils down to their impact on their local watershed. A watershed is a geographic region that drains into a common body of water, such as a stream, river or lake. Activity throughout a watershed impacts the quality of these bodies of water, as well as groundwater, wells and other sources of drinking water. Agriculture can be either a great boost to our water, or a great detriment.

Across the country, development remains one of the largest threats to watershed health. The increase in urban and suburban areas means there are more and more impervious surfaces—like pavement or sidewalks—that don’t allow rainwater to be absorbed into the soil. When that happens, nasty things like gasoline and oils, sediment and fertilizer, will end up as “runoff” in local waterways.

But open space preservation can be a critical strategy to maintaining water quality in areas of rapid development. Open space includes places like mature forests and meadows, but it also includes agricultural fields, which can run off half as much water as impervious surfaces. Of course, not all open space is the same. Mature ecosystems are better than bare soil, so adopting good soil stewardship practices like cover crops for fallow fields, diverse crop mixtures and reducing tillage on open soils are powerful strategies for farmers looking to protect their watersheds.

While agriculture can protect our watersheds, some agricultural practices have been notorious for deteriorating water quality. Excess fertilizers, herbicides and insecticides from agricultural lands (and residential areas), sediment runoff from poorly managed cropland, and bacteria and nutrients from poorly managed animal manure can create dire consequences in our waterways.

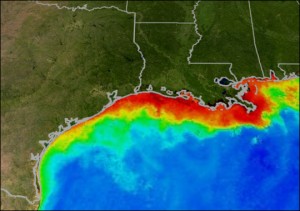

Excess nutrients found in runoff—notably nitrogen and phosphorous—can contribute to the excessive growth of plant life like algae in water bodies, which consume too much of the available oxygen in the water, creating “dead zones.” Dead zones are vast swaths of waters where life can no longer be supported; they occur in areas like the Great Lakes, Chesapeake Bay and throughout the Mississippi River Basin. According to the USDA, as much as 15 percent of the nitrogen fertilizer applied to cropland in the Mississippi River Basin makes its way to the Gulf of Mexico, where a dead zone as large as the state of New Jersey is so oxygen deprived, no fish can survive.[1]

Reducing Farming’s Water “Footprint”

In terms of water-guzzling capacity, farming is tops, far outpacing industrial and municipal uses. The most recent estimates from the U.S. Department of Agriculture are that 30 trillion gallons of water are used to irrigate 55 million acres of cropland. That amount is proving to be unsustainable in watersheds throughout the country, particularly in the West where persistent drought conditions are taxing already fragile reservoirs and rivers.

This point was made all the more clear last year, which presented the worst drought on record since the peak of the Dust Bowl in the 1930s. In the summer of 2012, almost 80% of U.S. farmland experienced drought, providing a clear picture of what’s at stake when water resources run short. Not only did it present dire circumstances for family farmers across the country, who watched their crops wither and their livestock suffer, but it caused spikes in food prices and has proven to be an extremely expensive problem. In the last decade, drought-related insurance and disaster payments have averaged $4 billion annually, up from an average $1.3 billion in the 1980s.

Climate change will bring more frequent and intense weather extremes like these, as well as flooding events like those currently threatening parts of the Midwest and Northeast. Both cases undermine the productive capacity of agriculture and highlight the critical need for proper water stewardship on our farms to build resiliency in our land and manage competition of our precious water resources.

Family Farm Solutions

Many family farmers who are engaged in alternative, smaller scale enterprises are already employing practices that serve our water quality. By growing more diverse crop mixtures, using strong soil stewardship measures (which increase the ability of the land to capture and store water), and implementing cover crops, buffer strips and other high vegetative areas to filter nutrients and buffer erosion, family farmers are turning around the watershed health in many parts of the country. In the Saratoga Lake Watershed, home of the Farm Aid 2013 annual benefit concert, farmers in the region (like this month’s Farmer Hero) are working together with fantastic land preservation and stewardship organizations to protect the quality of the Saratoga Lake watershed, which in turn contributes to the larger Hudson watershed, which in turn feeds into the Atlantic Ocean!

Did You Know?

By simply increasing organic matter in their fields by 5%, family farmers can increase their soil’s water storage capacity from 33 pounds per cubic meter to 195 pounds. That’s a 590% increase!

Experts are increasingly pointing to the importance of state and federal policy to address farming’s impact on our waterways. The policies set in the Farm Bill play a big part in whether we incentivize good on-farm water stewardship practices. But in too many parts of the country, farmers aren’t receiving the support they need to do so. For example, only 4% of farms in the U.S. use drip or precision irrigation systems, which are more efficient than traditional irrigation practices. Programs like the Environmental Quality Incentives Program could help farmers implement these new systems by off-setting the costs for implementation. For livestock producers, better pasture management and rotational grazing plans supported through the Conservation Reserve Program or the Grasslands Reserve Program can help the land cope with drought and flooding risks.

But most of the conservation programs in the Farm Bill are on the chopping block or set for massive cuts as the Senate and House debate the next farm bill. In the wake of climate-related disasters that all too clearly illustrate the fragility and interconnectedness of our food and water systems, we cannot afford to treat conservation programs as an afterthought. They are as essential to the long-term success of family farm agriculture and the quality of our food as anything, and represent some of the smartest, most forward-thinking policies our federal government has developed.

Sources

1. Dell’Amore, C. (2013). Biggest Dead Zone Ever Forecast in Gulf of Mexico. National Geographic Daily News. http://news.nationalgeographic.com/news/2013/06/130621-dead-zone-biggest-gulf-of-mexico-science-environment/

Further Reading

- Read our Farmer Hero profile of a New York farmer who is taking extra care to protect water and other natural resources as he raises grassfed beef.

- Learn more about the Gulf of Mexico “Dead Zone” on Wikipedia.