In this third episode of Against the Grain’s series on Artists and Activism, we talk to artists who come from farming backgrounds and have joined Farm Aid over the years to stand up for family farmers. We hear first from the legendary bluesman, Taj Mahal, who grew up picking tobacco and working on a dairy farm in Massachusetts before studying animal husbandry and agronomy in college. Like Taj, the other artists we talked to for this episode – Cassandra Lewis, Waylon Payne and Charley Crockett — see their musical lives deeply intertwined with their love of the land and commitment to showing up for family farmers.

Listen to the episode below. And, make sure to subscribe in your podcast app of choice!

Companion Video Playlist

Watch artists featured in this episode in this video playlist!

Taj Mahal is a towering musical figure – a legend who transcended the blues not by leaving them behind, but by revealing their magnificent scope to the world. “The blues is bigger than most people think,” he says. “You could hear Mozart play the blues. It might be more like a lament. It might be more melancholy. But I’m going to tell you: the blues is in there.”

If anyone knows where to find the blues, it’s Taj. A brilliant artist with a musicologist’s mind, he has pursued and elevated the roots of beloved sounds with boundless devotion and skill. Then, as he traced origins to the American South, the Caribbean, Africa, and elsewhere, he created entirely new sounds, over and over again. As a result, he’s not only a god to rock-and-roll icons such as Eric Clapton and the Rolling Stones, but also a hero to ambitious artists toiling in obscurity who are determined to combine sounds that have heretofore been ostracized from one another. No one is as simultaneously traditional and avant-garde.

Quantifying Taj’s significance is impossible, but people try anyway. A 2017 Grammy win for TajMo, his collaboration with Keb’ Mo’, brought his Grammy tally to three wins and 14 nominations, and underscored his undiminished relevance more than 50 years after his solo debut. Blues Hall of Fame membership, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Americana Music Association, and other honors punctuate his résumé. He appreciates the accolades, but his motivation lies elsewhere. “It’s not a hunger, not a lust or even a thirst,” Taj says of what drives him. “It’s just more knowledge of self — to realize that almost everything is right here. We’re so used to looking outside of ourselves for things, and it’s right here.”

Taj’s exploration of music began as an exploration of self. He was born in 1942 in Harlem to musical parents — his father was a jazz pianist with Caribbean roots; mother was a gospel-singing schoolteacher from South Carolina — who cultivated an appreciation for both personal history and the arts in their son. “I was raised really conscious of my African roots,” Taj says. “So I was trying to find out: where does what we do here connect to what we left there?” In the early 1950s, his family moved to Springfield, Massachusetts — a microcosmic melting pot for immigrants from across the globe: the Caribbean, the American South, Europe, the Mediterranean, Syria, Lebanon. “Music was everywhere,” he says. “Things were different in those days. There weren’t a lot of places that African Americans had to go out to entertain themselves. So people did a lot of entertaining in their homes. Friday or Saturday night, you’d move the furniture, mop and wax the floor, and set things up so people could pop over and hear all the music.” Musicians and friends from around the world passed through, ate home-cooked feasts, and led neighborhood jam sessions and dance parties in cozy living rooms.

From the beginning, Taj found the blues magnetic, even as most artists around him in the Northeast were exploring other sounds. “I could hear little strains of the blues coming through — you could feel that energy in the music that was being played,” he says. “I could also feel that energy of the blues inside myself.” Piano lessons didn’t stick — “I’d already heard what I wanted to play” — so when a blues guitarist from North Carolina moved in next door, Taj found an early mentor and was off.

For college, Taj attended the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He graduated after studying agriculture and animal husbandry. “I knew I’d like to connect myself to something on this planet that’s meaningful,” he says. “That’s why I was interested in agriculture and music. Those were the two things that I recognized even as a very young child that people are never going to do without.”

In 1964, Taj packed up and headed west. In Los Angeles, he formed six-piece the Rising Sons with Ry Cooder. The group opened for Otis Redding, the Temptations, and more, and recorded an album, but it wasn’t released until about 30 years later. “I guess that’s when they decided, ‘Whoa. I guess this guy is real,’” Taj says, with a hint of a smirk. He’s referring to record executives — a breed for whom he has little patience. “For me, playing the old music was a refuge from all the stupid stuff that was going on,” he says, pausing for a moment to point out commercialization’s limiting effects on what was both recorded and heard.

In 1967, Taj’s self-titled debut announced the arrival of bold young bluesman. The following year ushered in two milestones: sophomore album The Natch’l Blues dropped, and Taj performed in The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus, a film featuring performances from the Stones, The Who, Marianne Faithfull, Martha and the Vandellas, and others meant for the BBC but pulled and kept from public eyes until 1996. In 1969, full of music and only just beginning, Taj released Giant Step / De Ole Folks at Home, a massive double album that hinted at Taj’s refusal to be boxed in.

The 70s were a productive and ambitious recording period for Taj that included the Grammy-nominated soundtrack for the film Sounder. He began experimenting with global fusions and flirtations, signaling to listeners his restless intention to discover both new and old and disregard commercially imposed boundaries. In the 80s, Taj moved to Hawaii, and fell in love with sounds native to the island as he toured constantly, internationally. His gritty blues began to incorporate Latin, reggae, Caribbean, calypso, cajun, jazz, and more, all layered over a distinctly Afrocentric roots base he’d been raised to rediscover.

For Taj, the 90s were incredibly prolific. Back-to-back Grammy wins for the Best Contemporary Blues Album recognized two dynamic projects with the Phantom Blues Band: Señor Blues and Shoutin’ in Key. “I noticed that when it came to complicated pieces of blues music, they’d never get played,” Taj says. “It’s one of the reasons we put Señor Blues out — to say, ‘You guys, you know there is more that just the same old [imitates a beat] di da di di di da.’ It’s good when you believe it when you’re playing it. But just to play it as a cliche? That’s real boring. And real tiring.” Collaborations with Hawaiian, African, Indian, and other musicians helped define his decade.

Over the years, Taj had also emerged as a mind-boggling, multifaceted player. In addition to the guitar, he has become proficient on about 20 different instruments — and counting. “There weren’t an awful lot of people still playing these instruments that came from my culture,” Taj explains. “Not that they didn’t before, but nobody was playing them in the time I was. But I wanted to hear them. So I watched people play, got one, sat down, remembered the music that I was listening to, and started picking it out on the mandolin or banjo or 12-string.”

Taj didn’t slow down as he entered the 21st century. Maestro, marking the 40th anniversary of his recording career and featuring a global mix of voices ranging from Angelique Kidjo to Los Lobos to Ziggy Marley to Ben Harper, dropped in 2008. Last year, his highly anticipated collaboration with Keb’ Mo’ — TajMo — netted Taj his third Grammy. Several projects are currently in the works, as Taj remains excited by fresh young voices trying new things and exhumed treasures that have been buried too long.

As Taj thinks about the dozens and dozens of albums, collaborations, live experiences, and captured sounds, he finds satisfaction in one main idea. “As long as I’m never sitting here, saying to myself, ‘You know? You had an idea 50 years ago, and you didn’t follow through,’ I’m really happy,” he says. “It doesn’t even matter that other people get to hear it. It matters that I get to hear it — that I did it.”

Cassandra Lewis performs at Farm Aid 2024. Photo © Sharon Carone

Cassandra Lewis knows how to tell a story. She could go into detail about a childhood in constant motion, moving in a montage from Germany through Florida, Texas, and, eventually, Idaho among her family of “high mountain desert folk.” She shares memories of escaping loneliness and insecurity in front of the television set or tasting her first bit of fanfare as “a little yodeling cowgirl” at the town’s lone Walmart or retirement homes. There were moments of houselessness, working in countless restaurants, sleeping in a shared tent at a refugee camp, and selling joints “out of the back of a Subaru” that she lived out of with her rescue dog and cat after a wildfire burned down her farm in Mendocino. She found community in the Bay Area and if not for the integration of psilocybin and psychedelic medicine, she may have succumbed to the pitfalls of life instead of moving forward and using her pain to heal and forgive. She says she holds a deep gratitude for these dualities. “You can’t appreciate the light without living and breathing the dark.” She inhaled inspiration from cut-and-dry classic country and rock ‘n’ roll, smoked-out soulful psychedelia, and exhaled a shadowy signature sound—easily likened to a fever dream between Marty Robbins and Joni Mitchell. This is a new kind of cosmic Americana. She slung her songs for anyone who would listen only for a proverbial “last shot” to pay off by landing a deal with Low Country Sound/Elektra Records circa the pandemic. Now, she’s taking this foundation and paving her own yellow brick road on her 2024 full-length album, Lost in a Dream.

A son of country music royalty, a teenaged Baptist preacher turned addict and actor, Waylon Payne sings about fathers and sons, faith and addiction, recovery and renewal with devastating clarity. His character-rich collection harks back to a way of telling stories in song that revealed kept secrets and promised mystery. Over his years, Payne has felt the terrible power secrets can hold and learned the transformative value of releasing them. Finally, he’s in a place where he can harness that power to create transcendent work.

Payne recorded Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me primarily at Southern Ground Nashville, a converted century-old church building just off Music Row that once housed Monument Studios. Payne’s mother, country singer Sammi Smith, cut her iconic version of Kris Kristofferson’s “Help Me Make It Through the Night” at Monument. When Payne recorded his vocals, he says, “I stood in the same spot she stood and sang while she was pregnant with me.”

To help realize his musical vision, Payne worked with producers Eric Masse (Miranda Lambert, Rayland Baxter, Robert Ellis) and Frank Liddell (Lambert, Lee Ann Womack, Chris Knight) to assemble a group of musicians that spanned both genres and generations. In addition to highly regarded players like bassist Glenn Worf; guitarists Jedd Hughes, Ethan Ballinger, and Kris Donegan; and drummer Blake Oswald, the team brought in Cage the Elephant guitarist Nick Bockrath, as well as Mickey Raphael, Willie Nelson’s longtime harmonica player and a former band mate of Payne’s father, Jody Payne. Jerry Roe, like Payne a second-generation music man whose father spent years working for Johnny Cash, played both bass and drums. Other musicians on the album include longtime guitar player and friend Dean Person, slide guitarist Harrison Whitford, and violist Kristin Wilkinson, who arranged and conducted all the strings.

As a result, Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me sounds both timeless and out of time. It exists in music’s liminal spaces, the way the late ‘60s and early ‘70s albums of Kris Kristofferson and Bobbie Gentry did in their day. “Bobbie’s my songwriting hero, the reason I do what I do — her and Kris,” Payne says. “When my family threw me out, I picked the toughest motherfucker I could think of and modeled myself after him. I learned how to be a man watching Kristofferson.”

As a result, Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me sounds both timeless and out of time. It exists in music’s liminal spaces, the way the late ’60s and early ’70s albums of Kris Kristofferson and Bobbie Gentry did in their day. “Bobbie’s my songwriting hero, the reason I do what I do — her and Kris,” Payne says. “When my family threw me out, I picked the toughest motherfucker I could think of and modeled myself after him. I learned how to be a man watching Kristofferson.”

Like those artists, Payne draws from tradition while stretching beyond any notions of the mainstream, ultimately standing apart from everything else.

Payne has come a long way from the first time he and Liddell met back in the ’90s when Liddell worked for Decca Records. Payne showed up at Liddell’s office, unannounced, declaring his intentions to become a country star. It was the same sort of bold approach Tammy Wynette had made walking in on Billy Sherrill about a block away and 30 years before, and, like Wynette, Payne hadn’t brought any songs to bolster his case. Still, Liddell found Payne’s combination of raw talent, personal magnetism, and determination compelling, even if it still needed to be focused.

Payne eventually figured out how to harness those abilities, releasing his first album and launching an acting career that included portraying Jerry Lee Lewis in the 2005 Johnny Cash biopic Walk the Line and Nashville guitar legend Hank Garland in 2008’s Crazy. At the same time his career seemed to be coming together, though, a drug problem that had started in his teens was developing to a full-blown meth addiction that was ripping Payne’s life apart. “I was acting like a spoiled rock star,” he says. “By the time I started making movies, my ego was a little out there. Then you add meth to that, and you turn psychotic without realizing it.”

Now eight years clean, Payne finally can put all the elements of his life in their proper place. Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me testifies to a decade-long journey, capturing songs and moments from his most troubled time, as well as the grace and the relationships that led him out of it.

There’s tenderness to these songs, an empathy for lost souls who may or may not find their way home. Payne wrestles with the legacy of family dysfunctions in songs like “Sins of the Father” and “What A High Horse.” A pair of poignant vignettes, “Shiver” and “Old Blue Eyes,” team with tragedy and chilling beauty. “There are jewels buried deep in the record, and if you’re a junkie, you’ll catch them,” Payne says.

He views “Dangerous Criminal” as his point of reckoning. “It’s basically me admitting I have a problem,” he says. “I am a person who will get himself into trouble and in danger unless I keep myself in check.”

“After the Storm” and “Precious Thing” play like prayers, while “Santa Anna Winds” was written as a lullaby for the young boy whose voice is the first thing heard on the album, a child Payne views as almost a son and by whose first birthday he marks his sobriety. Payne also recorded his own version of “All the Trouble,” the GRAMMY- nominated song he wrote with Lee Ann Womack and Adam Wright and which Womack recorded for her 2017 album The Lonely, The Lonesome & The Gone. Payne’s talent as a songwriter has also been recognized by artists Ashely Monroe, Miranda Lambert and Wade Bowen, who have chosen to record his songs.

Payne may have recorded Blue Eyes, The Harlot, The Queer, The Pusher & Me in Nashville, but it started a decade ago in Texas, as he came through the worst of his addiction and got clean with the help of family and friends there. “For a while, I couldn’t even write,” he says. “I couldn’t put thoughts together, because I had really fried my brain. Once I got sober, everything came.”

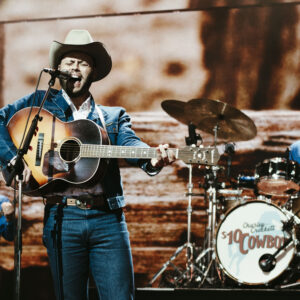

Charley Crockett performs at Farm Aid 2024. Photo © Sharon Carone

He picked up his first GRAMMY® nod earlier this year, and in the last year alone, he notably headlined Red Rocks Amphitheater in Morrison, CO, twice, played the Hollywood Bowl in Los Angeles, CA, and sold out two nights at the Ryman Auditorium in Nashville, TN. Speaking to his impact, CBS Mornings chronicled his journey, and he’s sat down for interviews on The Daily Show and most recently The Joe Rogan Experience. Plus, he’s graced the stage for performances on The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon, Austin City Limits, Jimmy Kimmel Live!, and CBS “Saturday Sessions” in addition to playing behind NPR Music’s “Tiny Desk.” With multi-GRAMMY® Award-winning Shooter Jennings as co-producer, the same unapologetic spirit, diehard work ethic, and no-nonsense honesty drive Crockett’s latest era, resulting in The Sagebrush Trilogy. Beginning with his Island Records debut Lonesome Drifter in March 2025, the trilogy continues with new album Dollar A Day, out less than five months later.

Episode 3: Artist Ag-tivists

FOLEY: Welcome back to another episode of Against the Grain: the Farm Aid podcast. I’m Michael Stewart Foley,

KURN: And I’m Jessica Ilyse Kurn. We’re in the middle of a series on artists and activism. If you’re just tuning in, head to our website, Farmaid.org/podcast and start with the intro episode.

FOLEY: So far in this series, we’ve learned a lot about the history of artists weighing in on social and political issues, about how artistic activism has been around for thousands of years, and how, for musicians, telling stories and song can both promote healing and move others to act in support of a cause.

KURN: If there’s one takeaway, I hope it’s an acknowledgement of how thoughtful and smart all of these artists are when talking about the issues that are important to them. Contrary to many critics’ charges that artists talk without substance, or worse, that they are using a cause for celebrity, in our experience, everyone we’ve spoken with has been extremely well informed. They’re even taking stands at the risk of losing audience.

FOLEY: Absolutely. The guests we’ll feature on this week’s episode include the legendary bluesman and Farm Aid artist Taj Mahal, as well as Waylon Payne, Cassandra Lewis, and Charley Crockett, who have also shared the FarmAaid stage. In this episode, we’ll speak with them about coming from farming backgrounds and showing up for family farmers to advocate for a farm and food system that’s better for all of us.

TAJ MAHAL SINGING

TAJ MAHAL: Yeah, hi, this is Taj Mahal.

KURN: That’s right. That was Taj Mahal, the legendary blues guitarist and singer, the kind of artist who brings down the house like he did at past Farm Aid festivals. Even when the house was a huge stadium, kind of like the University of Minnesota football stadium, where Farm Aid 40 will take place this September. We caught up with Taj just as it was getting dark at Willie Nelson’s yearly Luck Reunion festival near Austin, Texas this past March. It was about an hour before he was set to headline one of the festival stages.

FOLEY: What you might not know is that Taj Mahal grew up working the land and went to college to study agriculture.

TAJ MAHAL: You know, I spent my years picking tobacco from 14 to 16 and from 16 to 22, 24, I was working at a big dairy farm and going, and at the end, going to the University of Massachusetts, to get my degree in um animal husbandry and um minor in veterinary science, agronomy and dairy technology. But, you know, those days, they weren’t giving out the kind of loans that it would take to start a farm. So, the music kind of crept up from just being something personal that I did to being something that I could do my own way, you know, in the business and I came forward with that.

FOLEY: Pretty amazing, right? I live in Massachusetts and did not know until Taj told us that they grow Connecticut shade grown tobacco there. That’s the broad leaf tobacco used as cigar wrappers. Not only did I not know about that, but then I asked a dumb question. So you would have preferred to be a farmer before you were a musician?

TAJ MAHAL: Oh no, I would have been, I would have been a musician anyway. But farming,it’s separated here. In Africa, we don’t separate it – music, you know, it’s like you, when I was in Africa in ’79, we did 13 countries. But the thing was, is that when you said to an African, they said to you, they say to you, “what do you do, my brother?” And you say, uh, “I play music,” and they say, “yes, but what do you do?” So then I said, “I’m a farmer.” “Oh, no problem.” But they don’t, it’s like music is like breathing in that environment, you know? Here it’s a commodity because somebody’s making a lot of money off them.

KURN: “Music is like breathing.” I love that. And for Taj, that kind of breathing means lifting up and supporting the folks doing activist work. Here’s how Taj replied when we asked if he considers himself a political artist.

TAJ MAHAL: Yeah, and, in, in the sense that the music that I’m doing, who I am and where I came along in this whole thing, and continue to make it happen, that’s a political act. You know, I provide 100% of, um, you know, music for people who, who are responsible and accountable, and they need a place to go to hear some stories and some music to lift their spirit. That’s where I am. And that’s, and that to me, that’s, you know, am I gonna be running around with a placard? No, but that’s a political move as far as I’m concerned, because a lot of people spend at least 50%, sometimes 60% of their time railing against what it is they don’t like. But you know, it’s like, OK, so we all come out, we all put up a bunch of sides, we all holler, the police come and say, go home, and that’s the end of it. No, you have to do something in your life. So in my life, I provide, you know, uh, You know, relief from all of that stuff. And when you, it’s like, yeah, OK. When you come to listen to what I’m doing, you go like, well, how many years that guy, that guy’s been around 60 years doing that. And it’s not backed off. I have not backed off the accelerator belt.

FOLEY: And one of the ways Taj has shown up politically has been in support of farmers. As a guy who has worked the land himself and studied agriculture in college, he knows better than most the kind of odds family farmers are up against.

TAJ MAHAL: I’ve always been a, a supporter of, of the family farm and the small farmer. Can’t talk about the land of the free and then corporate agriculture is like running people out of business. It’s like, why can’t you make room for that? Why is it, why does it always have to be that kind of thing is that? But, yeah, and then when Willie got involved in, in Farm Aid and talked about the same kind of things that I was thinking about, and then some, you know, and it was an inclusive situations because I met the Federation of Southern Cooperatives here.

KURN: The Federation of Southern Cooperatives, which Farm Aid has worked closely with over the past 40 years, is an association of black farmers, landowners, and cooperatives that grew out of the civil rights movement.

FOLEY: It’s kind of amazing that Taj met the Federation of Southern Cooperatives at Farm Aid. This is what happens in the community that Farm Aid has cultivated over the past 40 years. What a treat to get to learn from a legend like Taj Mahal.

KURN: Next up, we’ll talk to first-time Farm Aid artist Cassandra Lewis to hear about her farming background and how it informs her artistic activism.

FOLEY: If you’re a farmer, Farm Aid is here for you. Our farmer resource network offers many ways for you to connect. Our goal is to link you up with helpful services, resources, and opportunities specific to your individual needs. Our hotline operators, who speak both English and Spanish, are available at 1-800-FARM-AID. That’s 1-800-327-6243, or can be reached online at Farmaid.org/podcast.

FOLEY: We got to sit down backstage with Cassandra following her spectacular performance at Farm Aid 2024 in Saratoga Springs, New York.

CASSANDRA LEWIS: My name’s Cassandra Lewis and I am here at Farm Aid, my very first Farm Aid and hopefully not my last.

FOLEY: Like the other artists in this episode, Cassandra comes from a farm family and has had her hands in the soil.

CASSANDRA LEWIS: Uh, my name is Cassandra Lewis. This is my very first Farm Aid and it’s been a dream of mine since I was little. It’s a true story. I joined the music business so that I could eventually afford to be a farmer. So I took a little circuitous path to uh to finally get back into my roots, which is how I grew up. And for me, music and farming has always been indivisible since the dawn of time, it’s been uh a collective, so I wanna, I just wanna bless and honor that today and all the people who are here working hard to bring food and music to our tables and our ears and our hearts. So we’re gonna get right into it and this song has absolutely nothing to do with farming.

KURN: After her set, Cassandra elaborated on how she introduced herself to the crowd.

CASSANDRA LEWIS: I’ve been a farmer and a musician for a long time and sort of, uh, dabble between the two and I’m working on integrating those things so that we can create a more sustainable touring and agricultural culture. So so that’s why I’m here. I [come from a] multi-generational farmer family growing up, uh. Mostly in southeast Idaho is where where my family is from, and uh it’s like right on the border of Wyoming. But I was an Army brat, traveled around quite a bit and then mostly settled there and so they were sheep farmers and um large crop farmers and also for survival as well any any any number of different animals or crops um and so I had those sort of values instilled and Yeah, I, I, it was a love of mine and also something I desperately wanted to leave as a as a kid (cause I’m like, I gotta go see what else is out there). Music was a means to do that and uh it’s interesting that music became a means to be able to go back as well.

FOLEY: It’s something we hear over and over again: how artists start out on the farm, many wanting to leave, but when they become successful, feeling the pull of farm life and looking to their art as a way to support a return to that way of life.

CASSANDRA LEWIS: Throughout my life I’ve worked in a lot of different farms, particularly in the cannabis realm and also vegetable farms and whatnot as a as a means to continue to do my music. You know, ultimately I saw a path forward for me and that’s through, you know, what is like the lowest hanging fruit for me, which is my voice, blessed be – you know, I’m very grateful to have that – and um you know, get this record deal recently with Elektra and have a have that that opportunity present itself as the most functional and clearest path to being able to get access to even just buying a little farm for myself, so. And a lot of the places that I’ve been and and traveled have have these incredible farms like out on the west coast. It’s like a lot of regenerative farm projects and and community based, land-based projects – and so they held me, and they gave me a home, and gave me a fire to sing around, and so that built my music, but it also kept me grounded while I was flying through space and time.

KURN: There’s something so special about the farming community. I can definitely see how sitting around a campfire on a regenerative farm can really regenerate the spirit too.

CASSANDRA LEWIS: There’s been a lot of division, especially lately, you know, just in, in, uh, in that, and so I’ve been just trying to kind of take a step back and not be so hardheaded and headfirst and really listen to what people want. It’s access to information based off of what is immediately necessary to you to survive. And while, we all have the same needs, right, to like the basic needs – Maslow’s hierarchy, right? – We need food, we need water, clean water, you know, we need joy, we need love. I think we need community desperately, and uh not this sort of, you know, bootstrap everybody, every man for himself kind of energy, but kind of go back to some of the old ways that we’re kind of almost more conservative anyways like helping each other in the in the community, give you the shirt off their back, and uh. We’re not so different, I think.

FOLEY: Imagine that: an approach to farming and rural life that, if we applied it to our national political life, could help us overcome the widely felt sense of division.

KURN: If only we could get the entire country around a campfire! When we come back, we’ll talk to Waylon Payne, another farm kid turned musician on this Artist and Activism series of Against the Grain.

KURN AD: If we all stand with farmers, we can make a real difference in our food system. Your donation to Farm Aid strengthens family farmers so they can thrive, and it keeps them on the land where they belong. Please make a gift today by heading to FarmAid.org/podcast.

WAYLON PAYNE: Hi, my name is Waylon Payne, and I’m a country music singing sensation. We are at Farm Aid in, uh, Saratoga Springs. That’s right, New York, and, uh. Charles Crockett is on right now and he’s just making me feel electrified in my chair.

FOLEY: It’s true: we conducted most of our Farm Aid 2024 interviews in a room just above the stage, so we not only could hear the music, but sometimes feel it vibrating through the building.

WAYLON PAYNE: I am so glad that I’m here. Thank God, uh, I’m in Willie’s band, so this is my second one that I’m able to participate in, uh, and it just, it makes me feel good. It brings a lot to my mind.

KURN: In fact, Waylon’s connection to Farm Aid goes back even further, because his dad, Jody Payne, was Willie’s lead guitarist from the early 1970s till about 2008. We’ll talk to Waylon about seeing some of the early Farm Aid festivals as a teen from backstage, and also about his father’s side of the family legacy in upcoming episodes. But right now, here’s Waylon talking about growing up with the other side of his country music family. His mom was the great country music singer Sammie Smith.

WAYLON PAYNE: Thinking back to my childhood and our family farm in Oklahoma, you know, it was my aunt and uncle’s parents, so they were like my grandparents, they raised me, you know. We all lived on family gardens. That was, that was what we did, and I was kind of wanting to call my sister Belinda and ask her like, what made us stop? Was it convenience of gentrification? Was it break up and the dispersal of the family? Because it always was a very harvest time, the garden time was always a family participation at our homestead in Marietta, Oklahoma, uh, at the at the fall crop and the spring crop, you know, summer crop, uh, there were canning parties, and we lived on that food that we grew for for years, you know, We had a storm cellar because it was the dust bowl and the tornado alley of Oklahoma, you know, that thing was stocked with all of our food that we ate.

I mean it was just what we did. we’re talking like, you know, quarts and quarts of food from potatoes, beans to corn to. Anything you wanted we had. We had a steady supply of potatoes because we knew how to preserve them in the garage, you know what I mean? It’s a lost art and it makes me very, very sad.

FOLEY: Between Waylon and Cassandra Lewis, I’m sensing a theme. I guess you’d say that family farms not only cultivate good food, but they’re cultivating a sense of community, of interdependence and mutual support. Like Cassandra, Waylon would like to bring that back.

WAYLON PAYNE: For the farm down in Alabama, uh, Jody, uh, and Vicky, my stepmom and my father, had, uh, about 6 acres – still do – and we’ve been talking for years about how we can make that thing productive. The soil’s rich. Jody, before he died, we brought in a couple of gardens and they were wonderful – changed my attitude about sweet potatoes. I’ve never liked them before, but I grew my own and I loved them, and, uh, there was something really, really healing and healthy about being hands in that soil because nothing else mattered. And I was so proud of that garden. We raised some good food that Thanksgiving we had delicious food that we grew and it was really nice and uh I believe we all need to get familiar with that again.

KURN: As Waylon spoke, you can tell, he got more and more animated as his vision of farm life morphed into self-reflection on what more he could do to support family farmers.

WAYLON PAYNE: Since I’m in the band now and part of the family – I’ve been a part of the family for a while, but I think I just gonna need to go ahead and play my part a little more serious because, uh, I love what you do, Willie, John, Dave, Neil, and Margo. It’s a good, good, good, good thing. So, uh, Waylon Payne says he’ll be here to do whatever you need.

FOLEY: Gotta love Waylon. You won’t want to miss him singing Help Me Make It Through the Night with Willie’s band. Waylon sings it every night as homage to his mom, Sammie Smith, whose version was a hit in 1970. Catch both performances at www.farmaid.org/podcast, where you can listen to companion playlists for each episode.

KURN: You may have heard Charley Crockett playing in the background there while we were talking to Waylon. After his set, he headed upstairs to our makeshift podcast studio above the stage and talked to us about his journey from farm to stage to advocating for farmers.

CHARLEY CROCKETT: Hello, I’m Charley Crockett. Here at Farm Aid 24. Well, Farm Aid is one of those things that that I can remember it being a thing even when I was a little boy because when Willie got it going and Neil and all them were getting and they could get everybody between them, they could get everybody to show up. I guess it’s one of those things that I never imagined that I would grow up and get invited to be a part of. It don’t matter what time you play at this thing, you know, just having an opportunity to get invited is. You know, to be here at the dance is enough.

FOLEY: This was Charley’s second Farm Aid festival, having first played at the 2022 show in Raleigh, North Carolina. And like Taj Mahal, Cassandra Lewis, and Waylon Payne, Charley comes out of a farm family and worked in the fields himself.

CHARLEY CROCKETT: Family wise, on my mama’s side – her father, my grandfather, my papa John, they were all sugar beet farmers from, uh, eastern Colorado actually – outside of Sterling, Colorado actually. My grandfather on the Crockett side is longtime rancher, but my experience with farming came after I ended up hoboing and, you know, turned into a transient and playing on street corners around America. I found my way into, I guess, being basically a migrant seasonal worker in the Pacific Northwest, you know, in, in ganja.

And I was telling I’ve been telling folks this all day. My mother was born in Denver, but she was raised, uh, partially in the Bay Area and then before her mama moved her back to Oklahoma, uh, where she was from rural Oklahoma, and then they come back down to Texas and that’s how, you know, I came to be and my daddy and them on the Crockett side they’re a bunch of generations back of Texans.

FOLEY: That bunch of generations of Texans goes back at least to Davy Crockett, one of the famed heroes who gave his life at the Battle of the Alamo. Charley got firsthand experience farming, not in Texas, but north of San Francisco.

CHARLEY CROCKETT: I was enamored by the idea of Northern California because the way my mama spoke about it as I was a child. It sounded to me based on her love for it, that if Big Rock Candy Mountain existed, it was up there. And so when I, when I started hitchhiking and hoboing, And I got a chance to get out there, I took that chance and I was just trying to get to Mendocino County. And when I got up there, what I found was, uh, a culture of, um, grape growers of old school horse ranches, people raising cattle, goats…Everybody in that county ate the eggs from their chickens on their land. I’ve never seen anything quite like that. We knew that our grandparents did that and saw that from a distance, but we sure as hell didn’t have that.

KURN: What Charley discovered was a community of small family farms growing all sorts of crops and raising livestock.

CHARLEY CROCKETT: I mean, people were raising pigs, growing weed, had a few grapes, doing their own vegetable gardens, doing cover crops, rotating crops, doing all that stuff, you know, using organic compost, talking about mycorrhizal and the soil, all this stuff that I’ve never heard anything about, you know, and and the folks that I was around, and I wasn’t, I’ve never been a good farmer, but I got pretty broad shoulders and I can move dirt pretty good, didn’t mind working all day. And it was like, you know, all you could eat, all you could smoke if you did, you held up your end of the deal. And these farmers like my music, you know, they were the first people that ever looked at me in the eye and valued what I did with a guitar as something that you could exchange, you know, as a, as an American, I guess (Texan first).

FOLEY: Yeah, something about those California farmers and supporting the music of both Cassandra Lewis and Charley Crockett.

KURN: This approach to farming resonated with Charley, more than school did and certainly more than the kind of farming he saw growing up in Texas.

CHARLEY CROCKETT: Where I’m from in South Texas, we lived in these little trailers and it’s surrounded by agriculture. It’s nothing but sugar cane and cotton and grapefruit, but by that time, you know, I was born in ’84, but even as a young kid, that all that work was being done by machines, you know, and what maybe a generation previously, a farm that took 20 to 60 people to run, they could do it with 4 or 5 people, even, even by that time. You know, with the machinery and all that. It’s interesting to be born in the 80s in a rural area where all that agriculture is around you. My daddy worked on shrimp boats and poured concrete and stuff, but I was right in the middle of it, but also disconnected from it.

FOLEY: So you can see why the approach to farming that Charley encountered in Mendocino might be more appealing. These days, Charley’s both committed to supporting Farm Aid and dreams of getting back to a farm life for himself one day.

CHARLEY CROCKETT: I mean, I look out the window on my bus all year round, you know, and it’s nothing but nothing but agriculture out there. It’s all cotton, cattle, both dairy and meat cattle, and then in the same fields of cotton, endless cotton are all the pump jacks, all the natural gas wells and on even beyond that is all the, uh, are now the windmills, the turbines. Part of me would love to be doing something in agriculture instead of what I’m doing, but that was, that, that’s, that’s not my place, you know, and I’m thinking about look like, you know, with Bob Dylan off-handed comment that he made that started this Willie on this whole path.

KURN: Naturally, this got us talking about Farm Aid and the challenges artists face when they want to step into the political arena lobbying for change. Charley said he was thinking about this during that morning’s Farm Aid press event.

CHARLEY CROCKETT: What I think is I’m looking at Willie today this morning out there, and he’s not doing the talking. Because Willie built the platform. He built the platform and it continues to provide the platform because Willie realized what he is best at. He realized what his most important contribution is, and he never forgot that, because even where I’m at right now with all the different business people and all the all the different political factions and all that… I’m not trying to walk the line and, and, uh, appease everybody. It’s that the things that I believe, if I want that to really be a real reality, if I want to have some kind of impact, the most important thing I can do is not let anybody knock me off the road that I’m on, you know? And if I start choosing sides too early in this landscape, they’ll just take me down.

And it is all in my songs if people want to know. It’s all there. You know, that’s what I was realizing looking at Willie: if I want to see some of the changes that I believe in, what I’m doing right now on stage is my best chance at pulling anything off. I think it’s so easy to forget that in the entertainment industry. They say, come over here and back these guys. Come over here and endorse this product. Here’s this half million dollars for this whiskey. It might cost you $5 million in authenticity, but don’t worry about that. I’m not on the left, I’m not on the right, I’m on the road. And that’s a dangerous place. That’s a dangerous place.

FOLEY: Yeah. That’s Charley Crockett playing Game I Can’t Win, a song about the very issue we were just discussing with him at Farm Aid 2024 in Saratoga Springs.

KURN: You can imagine it could be tough sticking to artistic authenticity when corporations are offering huge sums of money to endorse this product or that thing. Making a living as an artist is challenging, especially for those who came from rough beginnings. So do you stay true to your art and your community and the causes you care about, or do you cash in? The temptation has to weigh heavily at times.

FOLEY: In our next episode, we talked to several artists who try to lead with compassion and humanity, just trying to get people to be kind and decent to one another, and have caught flak for it.

EMILY NENNI: I want everybody at my shows to dance with who they want to and dress how they want to and and feel welcome and feel safe.

FOLEY: That was Emily NennI. We talked to her as well as Allison Russell, Grace Bowers, and Dylan LeBlanc in the next episode of Against the Grain.

KURN: Is there something you want us to cover in the future? Send us an email or drop a comment. You can email us at podcast@farmaid.org and find us on social media, which is at Farmaid on Instagram, Facebook, Threads and now on BlueSky.

FOLEY: And don’t forget YouTube, where you can watch almost 40 years of performances and other content. Let your friends know about Against the Grain. We’re beyond grateful when you listen, share, like and subscribe to this podcast.

KURN: Against the Grain was written and produced by us with sound editing by Endhouse Media and direction from Dawn Sorokin. And thanks to Micah Nelson for our awesome theme music.

FOLEY: Thanks so much to all the artists who took the time to speak with us. Head over to our website to watch videos, check out those playlists, and learn more. www.farmAid.org/podcast. And thanks to all the farmers out there. We’ll chat with you next time.

Listen to the Artists and Activism series of Against the Grain: The Farm Aid Podcast to hear from more than two dozen artists who use their art and voices as vehicles for political engagement and expression on issues that matter to them.

Listen to the Artists and Activism series of Against the Grain: The Farm Aid Podcast to hear from more than two dozen artists who use their art and voices as vehicles for political engagement and expression on issues that matter to them.