In this first episode of Against the Grain’s new series on Artists and Activism, we focus on the American folk music tradition. Music journalist Dorian Lynskey provides valuable historical context. He reminds us that music and politics have mixed from the beginning – even before the dawn of recorded sound – but that its folk musicians who popularized activist song and the trend of showing up in solidarity with those fighting oppression. We talk to folk musicians Steve Earle, Rainbow Girls, Tré Burt and Jesse Welles about activism in their music and how they use their music in their activism, as well as how they navigate the inevitable pushback that follows. Remember The Chicks being told to “shut up and sing!” following a statement about President George W. Bush and the Iraq War? We talk about that, too!

Listen to the episode below. And, make sure to subscribe in your podcast app of choice!

Companion Video Playlist

Watch artists featured in this episode in this companion video playlist!

Dorian Lynskey is a music journalist and writer whose has published in The Guardian, The Observer, MOJO, Billboard, Pitchfork, GQ, the Los Angeles Times, Village Voice, and many other publications. He is the author of three acclaimed books: 33 Revolutions Per Minute: A History of Protest Songs (2011), The Ministry of Truth: A Biography of George Orwell’s 1984 (2019), and Everything Must Go: The Stories We Tell About the End of the World (2024). He is also co-host of two of his own podcasts, Origin Story and Oh, God, What Now?

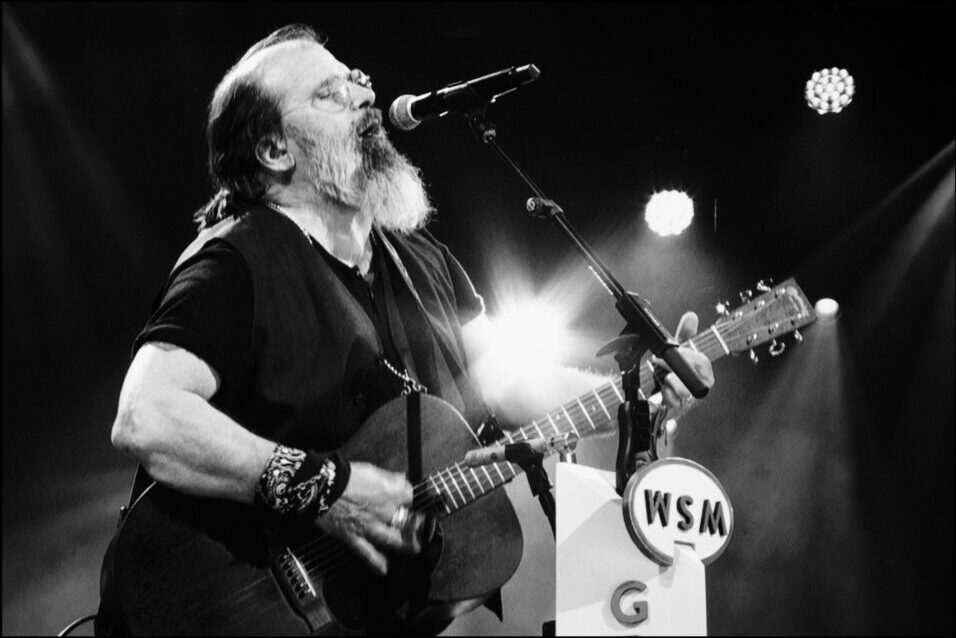

Steve Earle (Photo © Emma Delevante)

Steve Earle is one of the most acclaimed singer-songwriters of his generation. A protege of legendary songwriters Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, he quickly became a master storyteller in his own right, with his songs being recorded by Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings, Joan Baez, Emmylou Harris, The Pretenders, and countless others. 1986 saw the release of his record, Guitar Town, which shot to number one on the country charts and is now regarded as a classic of the Americana genre.

Most recently, Earle’s 1988 hit Copperhead Road was made an official state song of Tennessee in 2023. Subsequent releases like The Revolution Starts…Now (2004), Washington Square Serenade (2007), and TOWNES (2009) received consecutive GRAMMY® Awards. His most recent album, Jerry Jeff (2022) consisted of Earle’s versions of songs written by Jerry Jeff Walker, one of his mentors.

Earle has published both a novel I’ll Never Get Out Of This World Alive (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt 2011) and Dog House Roses, a collection of short stories (Houghton Mifflin 2003). Earle produced albums for other artists such as Joan Baez (Day After Tomorrow)and Lucinda Williams (Car Wheels On A Gravel Road)

As an actor, Earle has appeared in several films and had recurring roles in the HBO series The Wire and Tremé. In 2017, Earle appeared in the off-Broadway play Samara, for which he also wrote a score that The New York Times described as “exquisitely subliminal.” Earle wrote music for and appeared in Coal Country, for which he was nominated for a Drama Desk Award. Earle is the host of the weekly show Hard Core Troubadour on Sirius Radio’s Outlaw Country channel.

In 2020, Earle was inducted into the Nashville Songwriters Hall of Fame. And in 2023, Steve was honored by the Bruce Springsteen Archives & Center for American Music.

California indie band, Rainbow Girls, is known for their haunting harmonies, powerful songwriting, and unfiltered yet poised stage presence. Their live show is an unforgettable, one-of-a-kind experience that will make you both laugh and cry.

The band met in Southern California and formed at a weekly open mic night they hosted in their college house — known as Rainbow House. They spent their first few summers as a band, busking & couch-surfing across Europe on one-way plane tickets.

When their drummer left the band in 2016, Erin Chapin, Caitlin Gowdey, & Vanessa May pivoted toward a raw, stripped-down acoustic sound, performing around a single condenser mic. This spotlighted their intricate harmonies and cemented their place in the roots music scene. Since then, their blend of provocative charm and musical precision has earned them a cult following across the US and Europe, thanks in part to a viral rise on social media.

Their latest album, HAUNTING (2024), is both a sonic evolution and a bold reclamation. As Chapin puts it:

“The concept for this album came about from the word ‘haunting’ itself, which is the most common adjective people use when describing female harmonies. But what is it about female harmonies that make people want to describe them as ‘haunting?’ It’s because they’re powerful. And if a woman is powerful, then she must be a witch. She must be otherworldly or special because a regular woman couldn’t possibly be powerful on her own. We are reclaiming the word ‘haunting’ to describe our power – the power we find in reckoning with our trauma, grief, loss, and fear.”

The album dives deep into that reckoning — layered with grief and resilience, it’s an intimate yet expansive collection of songs that shine a light on the transformative nature of pain and the strength that grows from it. It’s Rainbow Girls at their most raw, most refined, and most powerful.

Photo by Mary Ellen Matthews

When Tré Burt was signed to John Prine’s Oh Boy Records in 2019, he was one of only two artists – including label mate Kelsey Waldon, to join the label in the past 15 years. Caught It From The Rye, Tré Burt’s debut album was re-released on Oh Boy in Jan 2020. The album showcases Burt’s literary songwriting and lo-fi, rootsy aesthetic, which he honed busking on the streets of San Francisco and traveling the world in search of inspiration. Like label mate and songwriting hero John Prine, Burt has a poet’s eye for detail, a surgeon’s sense of narrative precision and a folk singer’s natural knack for a timeless melody.

Caught It From The Rye is an urgent missive from an important new voice in songwriting.

For a songwriter who thoughtfully documents what he sees in the world, 2020, while challenging, was rich with inspiration. The year birthed the single, Under The Devil’s Knee, a song that continues the tradition of outspoken political folk songwriters of yore. It is an incredibly moving protest song tracing the lives of George Floyd, Eric Garner, and Breonna Taylor. Recorded remotely featuring Allison Russell, Sunny War, and Leyla McCalla.

Drawn to the guitar and songwriting in his early teens, Burt honed his literary songwriting and lo-fi, rootsy aesthetic busking on the streets of San Francisco and travelling the world in search of inspiration. He counts Richie Havens, Elizabeth Cotton and Townes Van Zandt among his influences,

He’s a songwriter who thoughtfully documents what he sees in the world. His 2020 single, “Under The Devil’s Knee”, continues the tradition of outspoken political folk songwriters – a protest song tracing the lives of George Floyd, Eric Garner, and Breonna Taylor. NPR said “Burt’s music expresses an ache for harmony, justice and solidarity.”

Currently signed to John Prine’s Oh Boy Records, he’s released two albums and an EP since 2020, and done a whole lot of performing and touring. A cohesive body of work and growing acclaim clearly illustrates the ever-expanding space in which Tré Burt’s voice belongs.

From the middle ages up to the modern era, society has leaned on its traveling troubadours for truthful commentary on the times. These folks trek from one town to the next, relaying the news, putting pain into words and healing with a little humor.

Jesse Welles unassumingly upholds and continues this tradition. Fearless, he reports from the frontlines of a divided country on the brink, addressing inequalities and injustices, cutting through all bullshit and driving directly to the source of the matter. His songs leave the same mark in front of a sold-out club as they do under the unbiased eye of a smartphone camera as he strums his guitar alone in the wilderness of Arkansas.

Jesse calls Ozark, Arkansas, home. You might’ve caught a glimpse of Ozark on the HBO documentary Meth Storm or in Paris Hilton’s reality television show Simple Life, but neither do it justice. With a population of 3,590, it’s a place where most families reside down dirt roads. The town consists of a turkey plant, an engine plant, a gas station or two and a handful of restaurants.

Growing up, his father worked as a mechanic, and his mom as a school teacher. Early on, his grandpa copied The Beatles’ White Album and Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band for Jesse. Those cassettes would become the soundtrack to endless hours of bike rides and treks through the woods, long bus rides to and from school, and walks to the library. At 12-years-old, he finally scrounged up enough to dough for a “$56 first act guitar from Walmart.” It became like another limb to the boy. Bringing the guitar everywhere, he played along to the radio, studied “what the grownups did” during impromptu jam sessions at parties and gleaned nuggets of wisdom from local old-timers. He fed his obsession by checking CDs out of the public library and ripping them to the family computer, embracing classics from Bob Dylan, Joni Mitchell, Joan Baez and Woody Guthrie. He experienced another revelation “as soon as YouTube made its way to Arkansas.”

“Once somebody showed me Led Zeppelin and Black Sabbath, I was fucked,” he laughs. “We had waited like 10 years for our library to get the internet. Then, the old Pentecostal women who worked there wouldn’t let me plug in my headphones!”

Not one to take such news lightly, he actually wrote a letter to the Franklin County Seat and received permission to return to the library (with headphones in tow). Throughout high school, he balanced school band, playing football,and maintaining his GPA with jobs as a waiter at a Chinese restaurant, a DJ at the local country radio station KDYN Real Country, and chain-sawing trees at a local nature reserve. Simultaneously, he wrote, recorded, and performed original music, selling CDs at school. Upon graduating, he transferred from University of Arkansas to John Brown University where he picked up a degree in Music Theory. He further cut his teeth as the frontman for rock band Dead Indian, while also moonlighting as a standup comedian with “some rough characters.”

Relocating to Nashville, he launched his eponymous band Welles, releasing music and touring incessantly. He logged 280 shows in a year, canvassing North America and Europe alongside the likes of Royal Blood, Highly Suspect, Greta Van Fleet, and Dead Sara. Dropped from his old label (mid-Pandemic), he quit a job at a vegan meat manufacturer and returned to Arkansas. He consciously put music on the backburner. Reading voraciously, he devoured books by everyone from Cormac McCarthy to Mary Oliver. He funneled his excess energy into running, completing and pacing half-marathons and marathons.

In February 2024, life changed again when dad suffered a heart attack. Sitting in his father’s hospital room with a Woody Guthrie biography on his lap, Jesse realized what he needed to do.

“I was like, ‘I’m going to sing the news’,” he recalls. “There was a lot of war going on. That was bugging me—on top of my own shit life. I’d done my best to give up music, but I couldn’t. I decided I’d do this.”

He walked into the Ozarks, placed his phone on a tripod, sang right to it and posted the performance. The ensuing series of videos made a seismic impact online. He impressively attracted over 1 million followers on Instagram by performing tunes like “Cancer,” “Fentanyl” and “War Isn’t Murder” out in the cold. On a creative tear, he served up two full-length albums, namely Hells Welles and Patchwork. Audience enthusiasm manifested on the road, and he sold out successive headline tours. Capping off 2024, he railed against the corruption of the healthcare system in the powerful polemic “United Health,” which Rolling Stone hailed as “a John Prine-like ballad.”

Jesse is speaking the kind of truth you can’t get on the news or on social media. This is the kind of truth that’s best shared with a microphone over the vibrations of an open chord.

“If my music helps you believe you can make art and tell the world how you feel, there would be nothing better,” he leaves off. “I hope you get those paints out of the garage or fill up your journal. Turn on your phone and say what you gotta say. There’s so much wild stuff in my head. I want to see where it can go.”

Episode 1: Folk Singers and Politics

KURN: Welcome back to Against the Grain, the Farm Aid podcast. This is episode 1 in our seven-part series on musical artists and activism. I’m Jessica Ilyse Kern.

FOLEY: And I’m Michael Stewart Foley. As you may know, this is Farm Aid’s 40th anniversary year, and we’re planning a huge celebration at our festival in Minneapolis in September. It’s going to be at the University of Minnesota football stadium. Check out all the details like this year’s lineup and about the venue at Farmaid.org/podcast. The festival is Farm Aid’s signature annual event where we raise awareness and the money that keeps the organization going all year – funding farm organizations, supporting the family farm movement through advocacy and public education, and staffing the only national hotline for farmers.

KURN: And that work would not be possible without the extraordinary generosity of artists who donate their time and talent each year, paying their band and crew and all the travel expenses. This year, like every year, the festival will feature something like 11 hours of music performed by artists committed to Farm Aid’s mission of keeping family farmers on the land. They come to stand together with and celebrate family farmers. If you know a bit about Farm Aid’s history, which we discussed way back in the first episode of Against the Grain, then you know that Farm Aid was founded in an era known for benefit concerts. Going back to the Concert for Bangladesh and the No Nukes concerts of the 1970s, and most famously Live Aid, a huge concert on two continents for Ethiopian famine relief.

FOLEY: There’s also all of the charity singles put out on record, like We Are the World. Musicians mobilizing to do good to support various humanitarian causes seemed pretty normal, almost routine, in 1985. But long before benefit concerts became a part of our culture, musical artists had been taking up social and political causes for decades, even before the advent of recorded sound. Some of the earliest American songs for a cause, songs we still know, may have been those sung by enslaved people in the 19th century. Songs like Swing Low Sweet Chariot, or Michael Rowed the Boat Ashore, were songs of faith, but also songs of leaving behind oppression and finding freedom in the Promised Land.

KURN: In this song, Wade in the Water, there are references to baptism and redemption, but many scholars believe that it was also meant as a reminder to fugitive slaves to walk in and cross streams and rivers as a way of throwing dogs off their scent. It’s so interesting that these songs originated with a social or political purpose, and most people don’t even know about that.

FOLEY: Yeah, and it turns out that popular music has always been a vehicle for activism. Remember World War One?

KURN: Uh, No

FOLEY: Yeah, me neither! But in 1915, before the United States even entered the war, Alfred Bryan’s I Didn’t Raise My Boy to Be a Soldier sold 650,000 copies of its sheet music to be played at home. This is 2 years before George M. Cohan’s pro-war song, Over There, became a hit.

KURN: Songs like these were played on early Victrola record players or on a piano. The kind of music and activism we think of today in America really started with folk singers, the traveling troubadours, who would show up to sing in support of striking workers at picket lines and in labor camps.

LYNSKEY: I think that political activism in American music starts with the folk scene, and if you go back to the, the Wobbly singer Joe Hill, who was an influence on Woody Guthrie, in the 1930s and 1940s, he was then an influence on Pete Seeger and a kind of mentor to Pete Seeger.

KURN: That’s Dorian Lynskey, the music journalist and author of 33 Revolutions Per Minute, A History of Protest Songs from Billie Holiday to Green Day. We caught up with him from his home in London.

LYNSKEY: And then through the 50s and this kind of winter of McCarthyism, you’ve got these really important figures, Seeger and his circle, keeping the spirit of the left alive within the folk scene, places like Highlander Folk School, um, which Martin Luther King visited and found a very very inspiring, where Seeger was partly responsible for writing We Shall Overcome, which became the anthem of the civil rights movement. So you had. Songwriting and activism and tied in together.

FOLEY: As Dorian explained, thanks to this trend of activist songwriting and showing up to support the labor movement and the civil rights movement, the folk music of the 1960s – think Bob Dylan or Joan Baez – goes on to inform more popular music later in the decade. Farm Aid board artist Neil Young and other artists like Joni Mitchell started out in folk, but as Doring points out, carried their political consciousness into rock and folk rock.

LYNSKEY: It’s not a hugely important part of early 1950s rock and roll, but it becomes via folk, massive during the 1960s. And then that has a knock-on effect. You know, Bob Dylan inspires Sam Cooke to write A Change Is Gonna Come. Protest becomes more of an aspect of soul music, and, and I would say, you know, by the time you get to the 1970s, soul music and the black music in general is, is far more consistently politically outspoken than than rocky.

KURN: Which is great because coming up after the break, we’ll talk to a bunch of folk musicians about their work. Stay with us.

KURN [promo]: For 40 years, Farm Aid has stood with family farmers against corporate power, bad policies, and climate disasters. As Farm Aid founder and president Willie Nelson says, “family farmers aren’t backing down and neither are we.” Head to our website to learn more, Farmaid.org/podcast.

FOLEY: Welcome back. For the past 2 years we’ve headed to the Luck Reunion Festival on Farm Aid founder Willie Nelson’s ranch in the Texas Hill Country just outside of Austin. This festival brings together musicians, chefs, and artisans who are contributing to American roots culture.

KURN: Between the dust and the heat, which kind of feels like a hot hair dryer blowing on you all day, we caught up with many artists, some who have played at Farm Aid and others who haven’t. One of the memorable interviews we’ve had was with Steve Earle, who has played a few Farm Aid concerts over the years. With recording gear in hand, we trekked through crowds and around the grounds of the festival to find Steve holed up in a vintage camping trailer with much needed air conditioning. He welcomed us in, and we crammed around a small round table to chat about music and politics and why he got into this realm as an artist.

EARLE: I’m Steve Earle. I’m a singer and a songwriter and some other stuff. You know, I don’t try to make any judgments about people one way or the other about whether they do it or not. I think it is a personal choice. For me, it’s not that big of a deal. It’s not that big of a choice. I basically came out of coffee houses, you know, so I’m essentially a folk singer. So there was always, and my first shows in front of people were happening in 1969 and 1970 and 1971, you know, and. (The first things I did that when the talent show at school) And, um, it was, things were pretty political. Vietnam War was going on and I was draft bait and um, you know, that’s why we were so much more politically active during that wars, the draft.

EARLE on stage: Yeah, wars are a tricky thing. The people that start wars are usually, it’s easy for them to do cause they’re not going. And their kids aren’t going. And it’s uh whichever side of this whole debate that we’re having about the war you’re on right at right now, I think it’s really important to remember that uh you know, George W. Bush’s kids are not gonna go. Dick Cheney’s kids are not gonna go. John Kerry’s kids are not gonna go. Your kids are gonna go. My boys are 17 and 22, and I think we need to have this discussion.

FOLEY: That was Steve Earle playing Rich Man’s War at Farm Aid 2004 outside of Seattle, Washington, two years into the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and two months before the presidential election. And don’t miss Steve playing this year at Farm Aid 40, on September 20th in Minneapolis.

One of the things I appreciate about folk singers like Steve Earle is the way they tell stories as a way to bring the listener to the issue. And sometimes, often, it comes from personal experience.

EARLE: My focus had been against the death penalty. That’s a tough one. That was an unpopular issue that I chose for myself, but I chose it because I’m from Texas. And, um, you know, it’s just one of those things that, that they were killing a lot of people and my mother. lived, you know, in, in Humble, like, you know, north of Houston, you know, really close, close enough to, to Huntsville that she felt like she could feel it when they started executing people. And so I got connected and I wrote a song called Billy Austin and people started calling me because of that. I guess because I’d been locked up for a very short period of time, inmates started writing me, and some of them were death row inmates. And so that’s connected me more and more to the issue. I finally ended up witnessing an execution in Texas, which I don’t recommend, but the guy asked me, and I didn’t know how you say no to that. It was a dying man’s last request. And my guys were all guilty that, uh, you know, innocent guys didn’t call me for some reason, and I’m, I’m opposed to the death penalty. Uh, my objection to the death penalty – It’s not about what it does to anybody on death row. It’s about keeping me from going to hell. It’s like, if this is a democracy, which that becomes more questionable every day, but if it is a democracy, then if the government executes someone, then, then, you know, I’m like, uh, that’s me, that’s, that’s being done in my name and, um, and I, I object to the damage that does to my spirit.

KURN: That was Steve Earle talking about his song Billy Austin. Steve also wrote a song called Over Yonder (Jonathan’s Song) about Jonathan Nobles, the inmate he knew personally and whose execution he talks about witnessing. That song is really worth a listen.

FOLEY: Yeah, that was pretty heavy. Later that same day, we caught up with some younger artists who write and perform in the same folk tradition as Steve Earle, but who weren’t even born when Steve Earle played his first few Farm Aid shows.

KURN Rainbow Girls are a group of three women from Northern California: Vanessa May, Caitlin Gowdy, and Erin Chapin, who have been getting a lot of attention not only in the US but also abroad.

MAY: We’re folk musicians at the end of the day, and for anyone to think that a folk musician wouldn’t speak their mind or speak truth to power and make sure that we advocate for women. That we advocate for people that are not white cis, heterosexual men. Um, they’re sorely mistaken. And if they see a way out the door, that’s totally OK. Don’t let it hit you on the way out.

KURN: That was Vanessa.

CHAPIN: Or stick around and maybe change your mind. Like I got to say it’s a little more fun to not just be boring.

KURN: That was Erin.

GOWDY: And it’s a lot easier to be afraid of someone or something that you have like this thing built up in your mind of who they are and what they stand for and if you’re actually in the same room with someone, it’s a lot harder to hate them if you have any kind of real conversation at all with another person.

KURN: And that was Caitlin. And as we talked, it became clear that not only do Rainbow Girls sing songs that are overtly political, but they view their very existence as a band, as a political act.

CHAPIN: I remember reading a quote by Joan Baez once and she said, this is not an exact quote, but she said she felt she was more of an activist, she was an activist first and a musician second, and I was like, Yeah, isn’t that the whole reason we’re doing this? It’s because when I grew up, I didn’t have any like female um idols who played music, who were like musicians who were in a band with other females. There’d be like a front person or like, you know, an awesome, but there’s been female musicians forever, but I didn’t really have an archetype to look up to, so to me it didn’t seem like it was possible. And then when we started this band, it was more to like prove a point that it could be possible. And then somewhere along the way we like actually tried to learn how to play our instruments better and harmonize in tune and just been just trying to sing in tune and like in time. All for social justice.

FOLEY: That was Rainbow Girls performing American Dream from their album, Rolling Dumpster Fire – coincidentally talking to us by the dumpsters, of all places, at Luck Ranch. When we come back, we talk to Tré Burt and Jesse Welles

KURN [promo]: If you’re a farmer, Farm Aid is here for you. Our farmer resource network offers many ways for you to connect. Our goal is to link you up with helpful services, resources, and opportunities specific to your individual needs. Our hotline operators who speak both English and Spanish are available at 1-800-FarmAid. That’s 1-800-327-6243, or can be reached online at Farmaid.org/podcast.

BURT: My name is Tré Burt. I’m a folk musician historically. Um, my boss is John Prine. I’m from Sacramento, California, and I’m the nephew of blues country, uh, folk singer Thomas Burt out of Piedmont County.

KURN: If you’re a fan of Farm Aid board artist Margo Price, or just a fan of good music, you might know Tré Burt. He opened for Margo on her Stray’s album tour, and we met up with him on that same day we talked to Steve Earle and Rainbow Girls.

FOLEY: We asked Tré about his approach to folk music and if he’d be comfortable calling himself a political artist.

BURT: Well, I, I guess I’d say that the personal is political. And whatever that means to the individual, um, and I’m pretty sure everybody cares about something so uh yes by that by that measure, I am a political artist uh I care a lot about humanity and what I see around me and, um, by those terms, I’m a political artist. I have a number of protest songs under my belt that range from talking about nuclear war, international war, um, violence against black community done by the police force, the public lynching of George Floyd, imperialism.

FOLEY: He’s so good, and he reminds me of Jesse Wells, another folk singer who’s been getting a lot of attention, enough that one of Farm Aid’s founders invited him to play Farm Aid 2024 in Saratoga Springs. You may have seen Jesse’s Power lines videos where he presents songs straight from the day’s news. But you might not know that Jesse has been playing and recording in bands for a long time, but after his dad had a health scare, Jesse decided to dedicate himself to making music, churning out songs in response to real-time events.

WELLES: You would never run out of material, um, that’s for sure, and uh you can only write so many love songs and so many uh drinking songs and so many horse songs and dog songs and truck songs… so top topical tunes. What got me into that? I, you probably listening to me try to make sense of the news and I like it better when it rhymes. And so that’s what I started doing just making making the news rhyme – to promote thinking, nonviolence and just peace above above all so in common sense, love your neighbor.

KURN: So where did that sentiment come from?

WELLES: That’s innate in all of us, we just have to get down to it. It’s the only way that anyone, anyone can survive, truly survive, truly be alive and love.

FOLEY: We asked Jesse about the folk music tradition and any artists he might see as role models.

WELLES: Absolutely I thought Woody Guthrie is the, is the template. He might be uniquely American. I don’t know if other cultures have that sort of thing, so if that is the case, it is uniquely American, but perhaps he feels the archetype of of of uh for humanity as like bard or news deliverer or something like that, so something much older than anything and as far as music industry is concerned or anything like that. But your job, I took it as my you take on a a duty of sorts or or a uh you make it your mission to go ahead and communicate what you see around you. That is really all that you can convey with any amount of authenticity is what you see around you. Um, if I was born in New York City, I’d be singing about tenement halls and I don’t know, subway fares or something like that. I would be singing about something else, but I was born and raised in Arkansas and so I sing about the crippling poverty that takes up all your time. And the ways that folks have been taken advantage of by larger corporations in those in those areas and stuff like that. There’s no shortage of things to write about. I don’t think there ever there ever will be because neither neither one side or the other really ever fix the real problems of hunger and hate. Neither seem to be proponents of food and love at the end of the day, so yeah.

FOLEY: Well, that’s why we work for Willie

WELLES: Yeah, uh, there’s, there’s only uh games that keep us divided. Yeah, that’s what I see at least.

KURN: That was Jesse Welles performing at Farm Aid 2024 in Saratoga Springs, New York. One of the things that comes up a lot when we talk to artists about engaging with social and political subjects is a kind of pushback they receive from the public, not unlike we discussed in the intro episode to the series, when the president went after Bruce Springsteen for some of the things he said on a recent tour.

FOLEY: Or when The Chicks spoke out about George W. Bush and the war in Iraq, and the message was similar: Keep your mouth shut! Just shut up and sing! There really can be a chilling effect on an artist’s right to free speech. Here’s Steve Earle talking about the inconsistent reactions that different artists get.

EARLE : You know, the Dixie Chicks, you know, as they were called then, you know, when that happened, I, I, I’m known, you know, Lloyd Maines, Natalie’s father is one of my oldest friends. And so I watched that really closely because I knew, you know, I knew her a little and, and, uh, I was connected to it in a lot of ways, but You know, they asked me why they didn’t react as strongly to, you know, when I walked out on stage at Shepherd’s Bush Empire, the same theater where Natalie made the statement that she did. I, I went on stage six days later with, uh, a, a t-shirt. I think it said “Fuck Bush” on it or something like that but I said “Fuck the War,” I guess. But I, I, I would have liked the one that said “Fuck Bush” at that point. I was pretty angry. And, um, and nobody really reacted that, and that’s because everybody by that point knew I was, you know, what my politics were, but it coming from girls, coming from women who were on country radio, this, there were people that saw it as a betrayal, and, uh, country radio itself the way they reacted it was sort of embarrassing to me because it’s like the real issue is like you’re scaring off some of our ideas so we can’t sell so much stuff. That’s why it made a difference. That’s what, that’s what the difference was was money.

KURN: Circling back to Dorian Lynskey, the music journalist and author of 33 Revolutions Per Minute, he told us why he thinks some artists get pushback and others don’t.

LYNSKEY: I think the amount of pushback you get is so context dependent. It depends what scene you’re working in, what the political climate at the time is. So Pete Seeger, who was hugely successful in the Weavers, the folk group, um, had massive pushback from the US government, just McCarthyism. You know, and he was called in front of uh HUAC to testify and refused to, you know, to refused to do so. Then you can look at somebody like John Lennon, who became identified as one of the most dangerous radicals in America when he moved to New York. And there were huge efforts there to persecute him, to deport him from the US.

KURN: Artists being attacked by the government, the media, and even the public for speaking their minds is not new. But as Steve Earle pointed out, why go after The Chicks in such a vicious way? And then just a few days later, when he expressed the same sentiment on the very same stage, there was no blowback at all.

LYNSKEY: I’m always thinking, I mean, what, what, what is it about the circumstances? What is it about the individual that draws so much heat? So you could say, for example, that when The Chicks in 2003 spoke out against President Bush and the Iraq war, was there a gendered element to the abuse they received? Absolutely. And you can see that in the documentary about them, the famous Entertainment Weekly cover where they were posed naked with all these kind of the the the insults have been thrown at them were painted on their bodies. But also it’s the fact that they were the darlings of the country scene and that you were, if you were outside country, you could speak out. If you were if you were Green Day, for example, or if you were a rapper, or even if you were Springsteen, you could speak out against the Iraq war and get much less flack, but there’s something about the fact that they were from Texas, that the country scene was in in this real sort of spasm of of patriotic fervor. So all these things sort of, all these things intersect, and I think once that heat turns on somebody, inevitably a lot of the criticisms they get will be gendered, will be racialized.

FOLEY: It’s true, whether there are comments from the stage or something recorded on vinyl. It’s just a statement, just a record. The listeners both appreciate their artists speaking up on issues that are important to them, or they really don’t like it. In our next episode, we’ll pick up on this theme by talking to a number of artists about how they navigate critics, how they help others through the creative process, and how they use storytelling as activism.

KYSHONA: There is something healing and you sharing your story, standing in your power, telling people your story, because you’re gonna help someone else in their healing process, right?

KURN: That was artist Kyshona. Come back next week to hear from her, as well as Farm Aid board artist Margo Price and Tammi Neilson on the next episode of Against the Grain.

FOLEY: Don’t miss the companion playlist for each episode, which can be found on our website, Farmaid.org/podcast.

KURN: Is there something you want us to cover in the future? Send us an email or drop a comment. You can email us at podcast@farmaid.org and find us on social media, which is @farmaid on Instagram, Facebook, Threads, and now on BlueSky.

FOLEY: And don’t forget YouTube, where you can watch almost 40 years of performances and other content. Let your friends know about Against the Grain. We’re beyond grateful when you listen, share, like and subscribe to this podcast.

KURN: Against the Grain was written and produced by us with sound editing by Endhouse Media and direction from Dawn Sorokin, and thanks to Micah Nelson for our awesome theme music.

FOLEY: Thanks so much to all the artists who took the time to speak with us. Head over to our website to watch videos, check out those playlists, and learn more: www.farmaid.org/podcast. And thanks to all the farmers out there. We’ll chat with you next time.

Against the Grain brings the magic of Farm Aid’s annual festival to listeners year-round. Hear from farmers and artists, advocates and food experts, activists and policymakers – all of whom are working towards building a more just and equitable farm and food system.

Against the Grain brings the magic of Farm Aid’s annual festival to listeners year-round. Hear from farmers and artists, advocates and food experts, activists and policymakers – all of whom are working towards building a more just and equitable farm and food system.